Elefant und Mensch – für das Volk der Kui gehören beide zusammen. Dieser innigen Verbundenheit hat Boonserm Premthada eine Freilicht-Anlage in Thailand gewidmet. In unserem Interview erklärt er seine Welt der ortsbezogenen Architektur.

13. Februar 2021 | Herbert Wright

S

urin, eine bewaldete Provinz im Landesinneren Thailands, ist die Heimat sowohl von Elefanten als auch von einem großen Teil der Kui (oder Kuy), einem einheimischen Volk in der Region. Die Beziehung zwischen den Kui und den Tieren hat sich zu einer Symbiose entwickelt; die Häuser der Kui werden sogar mit den Elefanten geteilt. Abholzung ist in Surin weit verbreitet, und der Tourismus hat die Elefanten ausgebeutet, was Grausamkeiten mit sich bringt und den Lebensraum und die Koexistenz von Kui und Elefanten stört. Die Dörfer der Kui sind arm. Elephant World, eine von der Provinzregierung entwickelte Touristenattraktion, versucht, all diese Probleme zu lösen. Die Anlage wurde neben einem Kui-Dorf auf einem Plateau errichtet, für das keine Bäume gefällt werden mussten. Die drei Hauptgebäude entstanden im Jahr 2020; der Entwurf stammt vom Bangkok Project Studio, das von Boonserm Premthada geleitet wird. Die Praxis legt Wert darauf, die handwerkliche Verarbeitung, Produktionsmethoden und Materialien der lokalen Region zu verwenden und mit modernen Elementen zu verbinden.

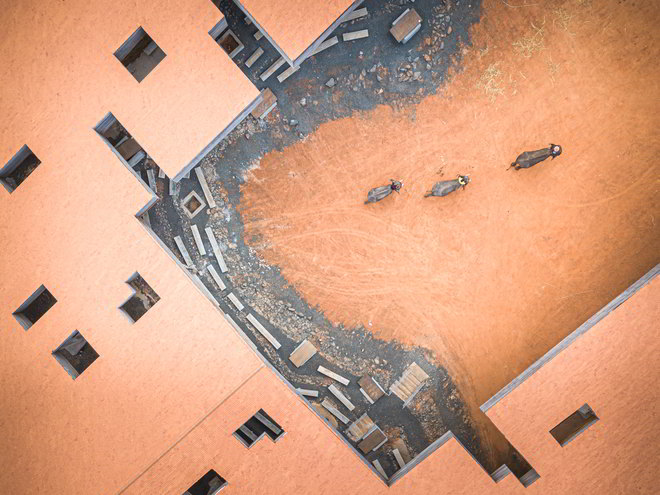

Das Elefantenmuseum ist ein Bauwerk, das sich in seinen orthogonalen Achsen sternförmig bis zu 140 m ausstreckt und 5.400 qm einnimmt. Die sich kreuzenden, begehbaren Wände sind aus mehr als 480.000 Ziegeln aus lokalem Lehm errichtet; sie wurden mit traditionellen Methoden handgefertigt. Von den Rändern aus steigen sie sanft an und bilden ein offenes, fast labyrinthartiges Netzwerk aus Gängen, groß genug für Elefanten und Höfen, von denen einige mit Wasserbecken ausgestattet sind. Außerdem gibt es vier Ausstellungsgalerien, in denen Exponate über die Kultur der Kui und über Elefanten zu finden sind.

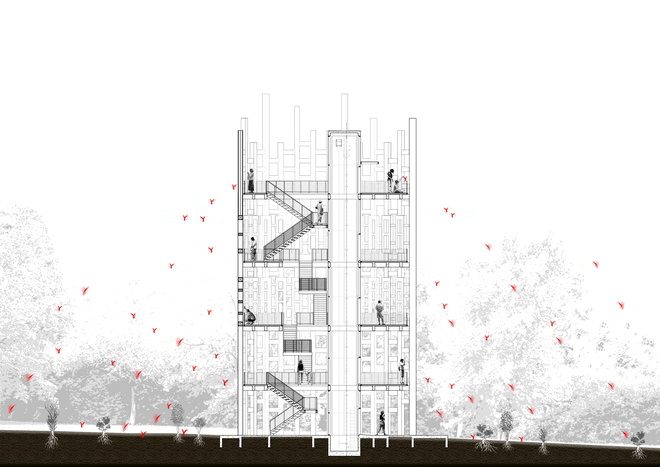

Der Brick Observation Tower ist eine 28 m hohe, durchlässige Struktur, die Wind und Sonneneinstrahlung mildert und sie in die inneren Treppenhäuser leitet. Er ermöglicht nicht nur einen Rundumblick über Elephant World, sondern bietet auch eine Aussaatplattform für die Samen des Apitong-Baumes, die der Aufforstung dient. Die Ziegel sind aus Materialien hergestellt, die für die Anlage eines Wasserreservoirs ausgegraben wurden.

Der Cultural Courtyard ist ein stattliches Gebäude mit einer Fläche von 8.130 qm, das nicht nur die Elefanten in den Mittelpunkt stellt, sondern auch eine geschützte landschaftliche Umgebung unter einem 70 m x 100 m großen, mit Holz verkleideten Dach schafft, das an die Satteldach-Architektur der Dorfhäuser erinnert, allerdings in großem Maßstab. Es ist so unterbrochen, dass Bäume hindurchwachsen können. Darunter befinden sich sechs bis zu 4 m hohe Hügel, die Bänke tragen und in einem Bogen angeordnet sind. Sie bestehen aus Erde, die für einen angrenzenden Regenwasser-Sammelteich ausgehoben wurde, um den Bedarf der Elefanten zu decken. Auch Basaltfelsen, die aus dem weiter entfernten Stausee abgebaut wurden, sind in die überdachte Landschaft mit einbezogen.

Boonserm Premthada erklärte sich bereit, unsere Fragen über das Elephant World Projekt zu beantworten.

Herbert Wright: Das Volk der Kui und ihre gemeinsame Kultur ist das Herzstück des Konzepts von Elephant World. In welcher Form wurden sie mit einbezogen? Gab es einen regelmäßigen Dialog und wurde die Zusammenarbeit auch während des Baus fortgesetzt?

Boonserm Premthada: Das Volk der Kui ist von Natur aus introvertiert und bescheiden und lebt nach seinen Überzeugungen. Für sie werden Elefanten von Engeln beschützt, und die Pflege von Elefanten ist eine Praxis, die seit der Zeit ihrer Vorfahren weitergeführt wird. Elefanten sind daher das Wichtigste im Leben der Kui. Sie sind Pflanzenfresser, daher sind Wälder, Pflanzen, Erde und Wasser für sie überlebenswichtig. Elefanten sind soziale Tiere; sie haben Geschwister und Eltern, genau wie wir. Elefanten aufzuziehen ist dasselbe wie Tiere aufzuziehen, aber man vergleicht es mit der Fürsorge für die eigenen Eltern, um Dankbarkeit zu zeigen. Elefanten können wie Menschen stur, clever oder ungestüm sein. Diese Verhaltensweisen beeinflussten die Gestaltung der Gebäude und der Landschaft. Die Beziehung zwischen dem Volk der Kui und mir verlief glatt. Von Baubeginn an bis heute haben wir das Gebiet weiterentwickelt, um Arbeitsplätze zu schaffen und Einkommen für die Gemeinschaft zu generieren.

HW: Hatten Sie die Gelegenheit, ein Kui-Haus zu besichtigen, das von seiner Familie mit Elefanten geteilt wurde, oder gehören solche Behausungen der Vergangenheit an? Wenn Sie eines gesehen haben: Was haben Sie dabei herausgefunden?

BP: Ich erhielt von den Dorfbewohnern die Erlaubnis, Vermessungsarbeit und Aufnahmen durchzuführen. Sie leben in Häusern, die komplett aus Holz gebaut sind. Die Dächer sind mit Zinkplatten gedeckt und die Böden hochgezogen, sodass unter den Hauptstrukturen offene Räume bleiben. Unter diesen Dächern leben auch Elefanten. Ich bin weltweit der Erste, der Häuser untersucht, in denen Elefanten und Menschen zusammen leben. Die Elefanten sind keine Haustiere, sondern Familienmitglieder. Diese Menschen verkaufen keine Elefanten, denn das wäre so, als würden sie ihre Nachkommen zum Verkauf anbieten. Von ihnen habe ich gelernt, Häuser zu bauen – als eine Form des Überlebens. Jedes Teil ist aus einem ganz bestimmten Grund da, aus einer Notwendigkeit heraus. Diese Häuser, die nicht von einem Architekten gebaut wurden, haben mich dazu inspiriert, für dieses Elephant-World-Projekt Bauten zu schaffen, die „nicht architektonisch“ sind.

HW: Wie unterscheidet sich die Erfahrung eines Elefanten mit seiner Umwelt von der eines Menschen? Gibt es neben dem Größenmaßstab und dem Wasser, dem Tummelplatz und den schattigen Stellen zusätzliche Faktoren, die das Projekt elefantenfreundlich machen?

BP: Das Elefantenmuseum versucht den Besuchern zu vermitteln, wie einzigartig die Sichtweise der Menschen in diesem historischen Dorf auf die Elefanten und die freundschaftliche Bindung zu den Elefanten ist, die sich ständig verbessert. In diesem Projekt sind Menschen und Elefanten ein untrennbares Element. Sie sind füreinander da. Die Regierung gibt jedem Elefanten ein monatliches Gehalt von 360 USD und 600 kg Napier-Gras pro Woche. Wenn ein Elefant stirbt, erhält der Dorfbewohner, der sich um ihn kümmert, kein Geld mehr. Deshalb müssen die Menschen ihr Bestes geben, um sich um die Elefanten zu kümmern. Sie sagten mir sogar: „Menschen können verhungern, aber Elefanten nicht.“ So sehen die Dorfbewohner ihre Elefanten.

HW: Das Elefantenmuseum ist auf die Unterbringung von Elefanten ausgelegt, aber ist seine Funktion nicht eher die, Menschen zu beherbergen? Betreten die Elefanten zum Beispiel die Pools im Innenhof, um sie zu nutzen?

BP: Ich habe den Gehweg als Eingang für die Elefanten in den Museumsbereich entworfen, wodurch den Besuchern signalisiert wird, dass die Elefanten Teil des Gebäudes sind – eine Nachahmung der Kui-Häuser, in denen die Elefanten leben. Die Anwesenheit dieser Tiere im Museum vermittelt das Gefühl eines Openair-Raumes. Die Architektur dient als Kulisse. Es ist ein Museum mit lebenden Objekten im Inneren, und das schafft ein Überraschungsmoment für die Besucher, während es gleichzeitig Menschen und Elefanten näher bringt.

HW: Die Verwendung lokaler Materialien und die volkstümliche Komponente (insbesondere beim Dach des Kulturhofs) verleihen dem Projekt eine starke Authentizität. Aber gibt es eine ebenso authentische Beziehung zu der schönen, komplexen und verzierten Architektur der lokalen Tempel?

BP: Mir sind der Ort und seine Geschichte immer wichtig. Im Elephant World Project respektiere ich die bestehenden Gebäude wie die Kui-Häuser, den Tempel, den Elefantenfriedhof und die natürlichen Ressourcen, einschließlich der Landschaften, Bäume, Hügel, Wege und lichten Wälder, die die Geschichte des Ortes und auch die Atmosphäre widerspiegeln, die einst von Menschenhand zerstört wurde. Das ist es, was ich den Menschen durch meine eigene Sicht, Denkweise und Einstellung zu diesem Landstrich vermitteln möchte. Ich möchte die Geschichte nicht imitieren.

HW: Sie verwenden Materialien, Hilfsmittel und Fertigkeiten aus der unmittelbaren Umgebung, aber auch Strukturbeton und Stahlelemente. Gibt es hier nicht einen Widerspruch zwischen lokalem, alteingesessenem kohlenstoffarmen Bauen und dem Einsatz moderner Materialien und Know-how?

BP: Die Begriffe „lokal, natürliche Ressourcen und Fertigkeiten“ haben für mich nicht den Beigeschmack, rückwärtsgewandt zu sein. Stattdessen beschreibt dieser Ausdruck die Richtung, in die sich die Welt bewegt. Was das Wort „modern“ angeht, so ist es so überstrapaziert worden, dass es fast bedeutungslos ist, weil man es überall antrifft. Meine Architektur setzt beim Materialdesign und bei Konstruktionsmethoden an, die lokale Bauherren ausführen können.

Alles basiert auf dem Wesen der Konstruktion und auf den Erbauern. Ich vertraue der menschlichen Intuition, um ein Gleichgewicht zwischen lokalen und industriellen Materialien oder handgefertigten Gegenständen und Technologie herzustellen. Beim Elephant World Project steht die menschliche Arbeitskraft im Mittelpunkt der Konstruktion, daher wurde der Großteil des Budgets in der Gemeinde verteilt. Stahl und Beton wurden nur sparsam verwendet, um die Gebäude stabil zu halten. In meiner Welt wird das Wort „lokal“ auf verschiedene Aspekte angewandt – lokale Materialien, lokale Konstruktion, lokale Ressourcen und lokale Fähigkeiten – als Zeichen dafür, dass man beginnt, sich von der menschenzentrierten Sichtweise zu entfernen.

HW: Im Jahr 2003 haben Sie das Bangkok Design Studio gegründet, und zwar in Bangkok, einer ziemlich großen Stadt. Elephant World versucht, die Natur wiederherzustellen. Kann die urbanisierte Menschheit jemals im Einklang mit der Natur leben?

BP: Oft ist der Mensch die Ursache für die angehäuften Probleme, mit denen wir konfrontiert sind, sei es Probleme zwischen den Menschen selbst oder Menschen gegenüber anderen Lebewesen oder Naturkatastrophen, Umweltverschmutzung usw. Der Egozentrismus ist zu einer „menschlichen Krise“ unserer Kultur geworden. Die Natur hat ein Leben. Berge, Bäume, Flüsse, Wind, Luft verdienen unseren Respekt. Sie können nicht von der Menschheit getrennt werden. Sie sind alle um uns herum. Inzwischen ist es der Mensch, der versucht, sich von der Natur zu distanzieren. Das Elephant World Project hat mich etwas über eine Zukunft des ausbalancierten Zusammenlebens gelehrt. Ich denke: An der Vergangenheit können wir nichts ändern, aber an der Zukunft können wir es. ♦

Übersetzung aus dem Englischen: Özlem Özdemir

HERBERT WRIGHT

Herbert Wright machte seinen Abschluss in Physik und Astrophysik an der University of London, war bis 2020 Contributing Editor des britischen Architektur-/Designmagazins Blueprint. Er hat Bücher über Wolkenkratzer und Urbanismus geschrieben. Seine neueste Autorenarbeit erscheint 2021 mit der Monografie „Mecanoo: People Place Purpose Poetry“.

Zur Website von

BANGKOK PROJECT STUDIO

Elephant World: Designing spaces that are good for companions bigger than us

Elephant and human – for the Kui people, the two belong together. Boonserm Premthada has dedicated an open-air facility in Thailand to this intimate bond. In our interview, he explains his world of site-specific architecture.

Surin, a forested inland province of Thailand, is home to both elephants and many of the Kui (or Kuy), an indigenous people of the region. The relationship between the Kui and the animal has become symbiotic, and Kui homes are even shared with elephants. Deforestation has spread in Surin, and tourism has exploited the elephants, bringing cruelty and disrupting the habitat and co-existence of Kui and elephants. Kui villages are poor. Elephant World, a tourist attraction developed by the provincial government, seeks to address all these issues. It is built beside a Kui village on a plateau site that required no trees to be cut down. The three principal buildings were completed in 2020 and designed by Bangkok Project Studio, led by Boonserm Premthada. The practice seeks to use local crafts, production methods and materials, in conjunction with modern elements.

The Elephant Museum is a structure extending like a star up to 140m in its orthogonal axes and covering 5,400 qm. Intersecting walls, which can be walked on, are built with more than 480,000 bricks of local loam, hand-made with traditional methods. They rise gently from its edges to form an open, almost maze-like network of passages big enough for elephants, and courtyards, some with pools. There are four exhibition galleries for presenting displays about the culture of Kui and elephant.

The Brick Observation Tower is a 28m-high permeable structure designed to moderate wind and sunshine, and bring them into the internal stairways. It allows not just views over Elephant World, but also provides a platform for the dispersal of Apitong tree seeds to aid reforestation. Its bricks were made from materials excavated to make a water reservoir.

The Cultural Courtyard is a grand building covering 8,130 qm that not only showcases the elephants but provides a sheltered landscaped environment under a roof of 70m x 100m, clad with wood, echoing the pitched-roof architecture of village houses but on a big scale. It is punctuated, so that trees may go through it. Beneath it, six mounds up to 4m high carry benches and are arranged in an arc. They are made from soil excavated for an adjacent rainwater collection pond to meet the elephants’ needs. Basalt rocks mined from the more distant reservoir are also incorporated in the covered landscape.

Boonserm Premthada was happy to answer our questions about the Elephant World project.

Herbert Wright: The Kui people and their shared culture are at the heart of the Elephant World concept. What form did consultation with them take? Was there a continuous dialogue, and did collaboration continue during construction?

Boonserm Premthada: The Kui people are introvert and humble in their nature and live according to their beliefs. To them, elephants are protected by angels, and caring for elephants is a practice that has been carried on since the time of their ancestors. Elephants are, thus, the most important thing in the life of the Kui. Elephants are herbivores, so forests, plants, soil and water are essential to their survival. Elephants are social animals; they have siblings and parents just like we do. Raising elephants is the same as raising animals, but it is compared to caring for one’s parents to show gratefulness. Elephants, like people, can be stubborn, smart, or fierce. These behaviours informed the design of buildings and landscape. The relationship between the Kui people and me has been smooth. From the day of construction to today, we have been continuing to develop the area to create jobs and generate incomes for the community.

HW: Did you have the opportunity to see a Kui home that was shared by its family with elephants, or are such housings now in the past? If you saw one, what did you learn?

BP: I was given permission from the villagers to conduct measure work and recording. They live in houses entirely made of wood. The roofs are covered with zinc plates and the floors are raised leaving open spaces underneath the main structures. Elephants also live under these roofs. I am the first in the world to study houses where elephants and people live together. Elephants are not pets, but family members. These people don’t sell elephants because it is just like putting their offspring up for sale. From them, I have learned to build houses as a means of survival. Every part is there for a reason, which is a necessity. These houses that weren’t made by an architect inspired me to create structures that are ‘non-architecture’ for this Elephant World project.

HW: How is an elephant’s experience of its environment different from a human’s? Are there additional factors, apart from scale and the water, romping soil and shade that make the project elephant-friendly?

BP: The Elephant Museum is trying to communicate with visitors the unique perspective that people in this historic village have about elephants and the friendly bond with elephants that is constantly improving. Together, people and elephants are one and inseparable element of this project. They are each other. The government gives each elephant a monthly salary of 360 USD and 600 kg of Napier grass per week. If an elephant dies, a villager who takes care of it will not receive the salary anymore. That is why people must do their best to take care of the elephants. They even told me, “People can starve, but elephants can’t.” This is how the villagers see their elephants.

HW: The Elephant Museum is scaled to accommodate elephants, but isn’t its function just to host humans? Do elephants enter, for example, to take advantage of the courtyard pools?

BP: I designed the walkway as an entrance for the elephants into the museum area, which shows visitors that the elephants are part of the building, to mimic Kui houses where the elephants live. The presence of these animals in the museum gives a feeling of an open-air space. The architecture serves as a backdrop. It is a museum with living things inside, and this creates a sense of surprise to visitors while bringing people and elephants closer at the same time.

HW: The use of local materials and the vernacular dimension (especially in the Cultural Courtyard roof) give strong authenticity to the project. But is there any relationship with the beautiful, complex and ornate architecture of local temples that is equally authentic?

BP: I always give my respect to the site and the history of the place. In the Elephant World Project, I respect the existing buildings, such as the Kui houses, the temple, the elephant cemetery, and natural resources, including landscapes, trees, mounds, paths, and sparse forests, which are the reflection of the history of the place and also the atmosphere that was once destroyed by human hands. That is what I want to communicate to people through my perspective, way of thinking, and attitude toward this area. I’d rather not imitate history.

HW: You use local materials, resources and skills, but also structural concrete and steel elements. Is there a contradiction between local, long-established low-carbon construction and using modern materials and know-how?

BP: The term “local, natural resources and skill” to me does not convey a connotation of being backward. Instead, this phrase describes the direction that the world is heading for. As for the word “modern,” it has been so overused that it is almost meaningless because you can see it everywhere. My architecture is started with material design and construction methods that local builders can do.

Everything is based on the nature of the construction and the builders. I rely on human intuition to strike a balance between local materials and industrial materials, or handmade items and technology. In the Elephant World Project, human labour is at the core of the construction, so most of the budget was circulated in the community. Steel and concrete were used sparingly only to keep buildings strong. In my world, the word “local” is applied to various aspects – local materials, local construction, local resources, and local skills – to show that humans are starting to move away from their human-centred point of view.

HW: In 2003, you founded Bangkok Design Studio in Bangkok, very much the big city. Elephant World attempts to restore nature. Can urbanised humanity ever live in harmony with nature?

BP: Oftentimes, humans are the root cause of these accumulated problems we are facing, whether problems between humans themselves or humans vs. other creatures or natural disasters, pollution, etc. Egocentrism has become a “human crisis” of our culture. Nature has a life. Mountains, trees, rivers, wind, air deserve our respect. They cannot be separated from humanity. They are all around us. Meanwhile, it’s the humans who try to distance themselves from nature. The Elephant World Project has taught me about a future of balanced coexistence. I think: We can’t change in the past but in the future, we can.

HERBERT WRIGHT

Herbert Wright graduated in physics and astrophysics from the University of London, was Contributing Editor of the British architecture/design magazine Blueprint until 2020. He has written books on skyscrapers and urbanism. His next authorial work will be published in 2021 within the monograph „Mecanoo: People Place Purpose Poetry“.