Üroborus_studioLab hat eine ehemalige Fahrstuhl-Fabrik in Taipeh wiederbelebt – heute bietet sie einen stimmungsvollen Raum für einen Aufzugsshop und kulturelle Events und präsentiert dabei zwei markante Gesichter

14. Juli 2023 | Özlem Özdemir

E

s kommt vor, dass man auf ein hübsches Wohnhaus stößt, das sich Villa Frieda nennt oder auf überwältigende Konstruktionen, die so aussehen, wie sie heißen, siehe das Atomiom in Brüssel. Diese Beispiele sind bekannt und sie verblüffen kaum. Dass man aber ausgerechnet einer ehemaligen Fabrik für Fahrstuhl-Achsenteile einen Namen verleiht? Die taiwanischen Architekten von Üroborus_studioLab (ein nicht minder interessanter Name) taten genau das bei ihrem revitalisierten Projekt QUAN Sphere.

Worauf deutet aber dieser Name hin – vor allem sein erster Teil? Auch wenn ein Fahrstuhl in Sachen Übergänge ein Spezialist ist: Mit Quantensprüngen dürfte er wohl nicht dienen. Nein, der Name gründet in etwas viel Naheliegenderem. „QUAN“, so verrät der leitende Architekt Hao-Chun Hung, „ist ursprünglich der Name des Vaters unseres Kunden.“1

Dieser Vater sah vor drei Jahren die Zeit für die nächste Generation gekommen: So übernahm sein Sohn die Fabrik. Der aber hatte Neues damit vor. Gemeinsam mit Hao-Chun Hung entwickelte er eine Lösung für eine neue Geschäftsidee: Achsenteile waren passé, entstehen sollte ein Aufzug-Auswahlshop, der die Kunden mit maßgeschneiderten Aufzügen versorgt. Der Architekt plädierte außerdem für ein lokales Kunstzentrum für die Gemeinde. Diese funktionale Mischung lag ihm besonders am Herzen; er hatte den Standort besichtigt und beobachtet, wie die Besitzer der kleinen Fabriken ihr ganzes Leben lang dort arbeiten, wie sie ständig produzieren müssen, um Geld zu verdienen. Hao-Chun Hung sagt hierzu: „Sie wissen nicht, wie man in diesem Industriegebiet gut leben kann, also wollten wir das in diesen Ort bringen.“2

Sanchongdingkan, so heißt der Ort, ist das erste geplante Industriegebiet der Region und liegt an der Nordspitze der Insel Taiwan, unweit vom Zentrum der Hauptstadt Taipeh. Es stammt aus den 1960er-Jahren; einst eines der wichtigsten Industriezentren, ist es heute nur schwach beleuchtet und beherbergt Familienbetriebe mit rostigen Maschinen. Die Umgebung von QUAN gleicht einer eintönigen Reihenhaussiedlung. Alle Bauten haben nur zwei oder drei Stockwerke; typisch sind ihre kleinen Vordächer im untersten Geschoss und ihre flachen Giebeldächer. Sie alle bestehen aus grauem Beton und ähneln sich auch ansonsten in ihrer Architektur allzu sehr.

Dieser Anblick und das Ambiente dieses Areals, erinnert an „Bonjour Tristesse“ – die Worte, die einst Unbekannte an die trostlose Fassade eines neuen Wohnhauses in Berlin gesprüht hatten. (Entstanden war es im Rahmen der Internationalen Bauausstellung 1984 und stammt ausgerechnet von Álvaro Siza, der in seinem Heimatland Portugal seine Bauten in durchgehendem Weiß erstrahlen lässt.) Das Grau der Fassaden von QUAN und Nachbarschaft erinnert an genau diesen äußerlich tristen Zustand. Wozu aber ein so weit hergeholter Vergleich? Der Punkt ist: Bei einem berühmten Berliner Beispiel eines sozialen Wohnungsbaus verwundert es nicht, wenn er wegen seiner nüchternen, wenig menschlich wirkenden Erscheinung kritisiert wird – das aber heißt nicht, dass ein Bauwerk mit industriellem Hintergrund keine Ansprüche stellen dürfte außer nur rein funktionale. Er darf.

Radikalität aber gehört nicht zu den Mitteln von Hao-Chun Hung. Er lässt den Vorgänger von QUAN nicht völlig aus der Reihe tanzen. Er lässt ihn nicht schrill werden und auch nicht aufhübschen. Vielmehr bewahrt er die Substanz und rührt nicht einmal an dem Grau seiner Fassaden. Er verdrängt nicht gänzlich den ursprünglichen Charakter des Vorgängers, der eine Stätte der Produktion war und nun zu einer Stätte der Präsentation und des Verkaufs wird. Was die Funktion betrifft, erweitert er sie nur. Doch da das Gebäude nun ferner auf Kultur und Publikum abzielt, muss es sich auch interessant machen. Die eigentliche Neuheit liegt also in seiner Ausstrahlung und Atmosphäre. Dafür verwendet der Architekt Mittel, Techniken und Materialien, die im Ort zu wurzeln scheinen und doch einen exotischen Effekt erzielen.

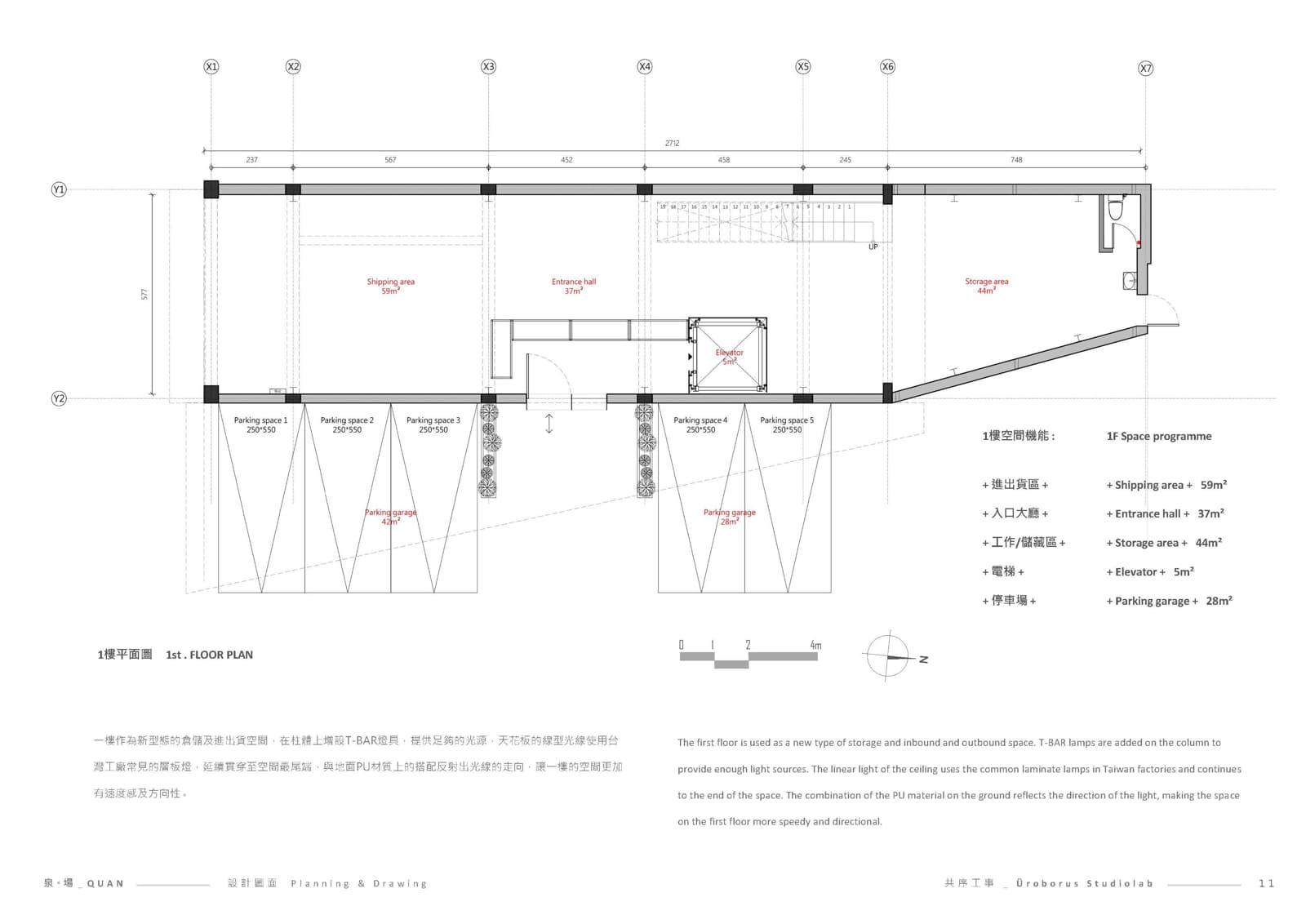

Die erste Ebene der Erneuerung, die der Funktion, ist schlicht: Das 145 m2 große Erdgeschoss dient nun als ein Raum für die Ein- und Auslagerung der Ware. Die Seite mit der schmalen Straßenfront kann im Erdgeschoss nur mit einem Rollladen geschlossen werden. Wenn er hochgezogen ist, ergibt sich der Eindruck eines großen Tunneleingangs. Dahinter ist der Bereich fast völlig unversperrt und diese Offenheit ist sinnvoll für einen Versandbetrieb. Auf der Längsseite hat das Erdgeschoss nur eine Tür, die – wenn man von draußen hereinkommt – direkt zur Tür des Aufzugs führt. Der erste Stock beherbergt das Büro des Unternehmers und einen Empfangs- und Besprechungsbereich. Und im zweiten Stock kommt schließlich das Herzensanliegen des Architekten zum Zuge, das Leben der Menschen in der Umgebung zu bereichern: Diese oberste Zone ist, wie zur Krönung, gedacht für kulturelle und künstlerische Events, Lesungen und Ausstellungen. (Das Angebot wurde bereits angenommen: Kurz nach der Fertigstellung von QUAN im letzten Jahr präsentierten hier drei Künstler ihre Arbeiten – das Thema ihrer Werke war die Wiederverwendung von Industriematerialien zur Schaffung von Kunstwerken.)

Die zweite Ebene der Erneuerung, die der Ausstrahlung und Atmosphäre, ist subtiler. Das betrifft nicht nur die Innenräume, sondern auch die Gebäudehülle. Wenn man auf QUAN zugeht, fällt auf, dass es ein Endgebäude mit zwei charakteristischen Seiten ist. Und diese Fassaden behandelt das Büro betont bis fast irritierend unterschiedlich.

Zehn Zentimeter vor der schmalen Seite ist eine Metallstruktur vorgelagert. Deren vertikale und horizontale Vierkantrohre sollen, laut Büro, an die Telefonmasten und Drähte der Umgebung erinnern. Die Struktur ist so gestaltet, dass sie vor der regellosen Fassade – die völlig sichtbar bleibt – ein System aus Linien und Rechtecken aufbaut. Darin eingepasst gibt es mehrere Rahmen aus 62 cm tiefen Edelstahlblechen, die den Fenstern Sonnenschutz bieten. Zugleich haben diese Rahmen eine ästhetische Funktion; sie zeichnen die Fenster nach und binden sie in ein übergeordnetes Schema ein. Das oberste langgestreckte Fenster und die vier Fenster im ersten Stock entkommen so ihrer Beliebigkeit; sie werden weder verändert, noch vertuscht, sondern dienen als Basis für ein neues Gestaltungskonzept. Außerdem verleiht die vorgelagerte Struktur der alten Fassade Charakter; sie erhält einen maschinell-industriellen Touch. Damit reflektiert sie aber nicht nur Telefondrähte und dergleichen, sondern erinnert auch an das ehemalige Fabrikthema des Gebäudes.

Die lange Seite von QUAN zeigt ein ganz anderes, gleichsam verschleiertes Gesicht à la Christo und Jeanne-Claude. Zehn Zentimeter abgesetzt von der bestehenden Fassade – die nur zwei kleine und ein großes Fenster, sowie den Haupteingang aufzuweisen hat – liegt wieder eine Struktur. Sie wirkt leichter als die andere, ist aus verzinktem Rohr und dient als Unterlage für das eigentliche neue Oberflächenmaterial: ein silbrig-netzartiges Tuch, das bei Blumenzucht, Teeplantagen und Landwirtschaft unter anderem zur Beschattung und Abdeckung verwendet wird. Bei QUAN steigt es auf zu einem dauerhaften Fassadenmaterial – sei es, um die dürftige Gestaltung dieser Gebäudeseite zu verbergen, sei es, um im Innern für eine introvertierte oder konzentrierte Stimmung zu sorgen. (Die Dichte des Gewebes übrigens ändert sich bei QUAN je nach Erfordernis; die Bandbreite beträgt 50 – 80%). Es ist mutig, wie die Architekten diesem Typ von Gebäude ein artfremdes, ein geheimnisvolles Attribut verpassen. Das Alte wird zu etwas Dahinterliegendem und Versteckten und lässt sich nur erahnen. Das flache Giebeldach verkommt zu einem bloßen Schemen, doch erst durch dieses Durchschimmern wird einem die Dachform erst richtig bewusst.

Ein Problem der langen Seite haben die Architekten besonders raffiniert gelöst: Wie und wo kann dieses leichte Rohrgerüst und die hauchfeine durchgehende Schicht nach unten hin enden? Immerhin liegt dort der Haupteingang. Sie entschieden sich für eine Geste, die ganz in der Natur des Stoffmaterials liegt. Dazu brauchten sie es nur am unteren Ende anzuheben – also im Bereich der Tür, für die man diese durchgehende Schicht ungern durchbrochen hätte. Das hat einen nützlichen Nebeneffekt: Wie von allein entsteht ein Vordach. Es wird nur von filigranen Stangen gehalten und ist groß genug ist, um Schutz für die darunterliegenden Parkplätze zu bieten. Im Endeffekt karikiert es die anderen Vordächer der Umgebung. Aber die Herleitung der Längsseite wäre auch andersherum denkbar: Vielleicht stand am Anfang gar nicht das schlichte Verdecken der Fassade, was schließlich zu diesem Vordach führte, sondern es war dieser ortsspezifische Typ von Vordach, der als Vorlage genommen und nach oben hin erweitert wurde und so erst der Effekt eines Vorhangs oder Schirms (mit unterem Knick) entstand.

Warum sind beide Seiten von QUAN so unterschiedlich – so sehr, dass der Fotograf es offensichtlich nicht wagte, eine Aufnahme von der Ecke aus zu machen? Warum tendiert die eine Seite zu einer industriellen Sprache und die andere zu einer künstlerischen, fast poetischen? Auffällig ist auch der Kontrast des Strukturellen der einen und des Texturhaften der anderen Seite. Der irritierende Gegensatz beiseite: Was beide eint, ist nicht nur das metallische, gräuliche Element; vor allem ist es die spielerische Haltung, mit denen die Architekten die Telefonkabel und Vordächer und nicht zuletzt das Zusammentreffen von Industrie und Kultur aufgreifen.

Auch die Innenräume erhalten eine neue Ausstrahlung und Stimmung. Das Licht ist hierbei ein wichtiger Akteur, unterstützt von den Oberflächen, denen die Architekten besondere Aufmerksamkeit schenkten. Diese vielen Mittel und ihre Einsatzstellen können nur beispielhaft aufgeführt werden.

Im Erdgeschoss ist eines unübersehbar: der vorherrschende Eindruck von Grau, das gleichsam von der Straße und der Umgebung hereingelangt ist (ein Farbauftakt, der sich durch das gesamte Innere zieht). Die Wände sind aber wie absichtlich verwaschen und der Boden ist mit PU-Material so behandelt, dass er glänzt. Diese Behandlungen lassen die Innenflächen des Gebäudes lebendig erscheinen. Aber diese Lebendigkeit wird erst sichtbar durch die künstlichen Lichtquellen, die den praktisch fensterlosen Raum erhellen. Von ihnen gibt es zwei Sorten: Die T-BAR-Lampen an den Säulen (die die Architekten von der Decke der ehemaligen Fabrik übernahmen und in eine vertikale Position brachten) und die versetzt angeordneten Laminatlampen der neugestalteten Decke. Letztere durchlaufen das gesamte Erdgeschoss, was ihn (zumindest im leeren Zustand) luftig und weit macht. Die Lichtreflexionen lassen den PU-Boden (der auch in den oberen Etagen auftaucht) wie wässrig, poliert oder lackiert wirken und die Richtungsbetonung der Deckenleuchten sorgt für den Eindruck von Geschwindigkeit und Dynamik.

Und in den oberen Geschossen gehen die Vitalisierungsmaßnahmen noch weiter. Dort sind die Innenwände in Teilen mit silbern schimmernden Trapezblechen abgedeckt. (Auch sie sind ein Nachlass des Originalbaus.) Im zweiten Stock zeigt das silberne Netz der Fassade, was es kann: Es filtert das Licht der Morgensonne und wehrt damit nicht nur die Hitze der Außenluft ab, sondern moduliert auch die Stimmung. Des Weiteren ist es eine schmale Treppe zum ersten Geschoss, die zum modernen Flair des erneuerten Gebäudes beiträgt. Die Struktur ihres Geländers aus Stahl (drei vertikale Flachstähle pro Stufe) korrespondiert mit der vertikalen Struktur des Trapezblechs der Innenwände.

Die Liebe zum Detail und die Lust an der Wahrnehmung durchzieht das gesamte Gebäude. Schon beim Öffnen der Tür gibt es etwas zum Staunen und Fragen: Ihre quadratische Klinke lässt (über eine Glasabdeckung) „tief blicken“; sie hat einen rätselhaften Inhalt, der an Eisenspäne erinnert und es handelt sich tatsächlich um Abfälle aus der Produktion der Aufzugfabrik.

Wie gesagt: Für einen Quantensprung soll „QUAN“ nicht stehen. Dafür bleibt das Projekt dem Prinzip der Lokalität zu sehr verhaftet. Die Architekten nutzen vielmehr das Gegebene als Rohstoff; sie veredeln und betonen es. Sie entdecken es und bereiten es so zu, dass es sich entdecken lässt. Das Vorhergehende und Alte bleibt ablesbar. Aus einem unscheinbaren Bauwerk in einer verbrauchten, überholten, freudlosen Industriesiedlung mit steifem Formenkanon erwächst eine individuelle, moderne, leicht-lockere, teils authentische, teils entfremdete, belebende Ästhetik, die nicht zuletzt eines erzeugt: Neugier. Das Wort „Quan“, so verrät der Architekt ferner, bedeutet auf Chinesisch Frühling (泉). Und das passt. Dieses Gebäude ist ganz QUAN. Es ist ganz Frühling. Sowohl der Baukörper als auch der Name kündet von Wechsel und Neuanfang. Man darf sich nur nicht von der Farblosigkeit täuschen lassen – auch nicht vom Halbdunklen oder Halbhellen im Innern, bei dem der Schriftsteller Tanizaki aufgemerkt hätte. Kurzum: Was hier passiert, ist erfrischend. ♦

¹ In einer E-Mail-Konversation zwischen Özlem Özdemir und Hao-Chun Hung im Juni 2023

² https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-03-04/an-elevator-maker-lifts-up-an-old-factory-in-taiwan; letzter Zugriff 14.7.2023 (Übers. v. d. A.)