Sir John Soane, Baumeister des Regency und Meister des Zeichnens, besaß Zehntausende von Architekturdarstellungen. Vom 22. 9. 2022 bis 15. 1. 2023 gibt die Tchoban Foundation in Berlin zum vierten Mal einen kleinen Einblick in seine große Kunst der analogen Visualisierung.

7. September 2022 | Özlem Özdemir

S

ir John Soane, ein produktiver Baumeister und besessener Sammler, gehört zu den interessantesten Figuren der europäischen Architekturgeschichte. Als Sohn eines Maurers kam er 1753 in der Grafschaft Oxfordshire zur Welt und wurde zu einem prominenten Architekten der britischen Regency-Ära, auch wenn seine Entwürfe nicht selten unrealisiert blieben. Innerhalb von 50 Jahren arbeitete er an einer Vielzahl von außergewöhnlichen Projekten. Zu seinen bekanntesten Arbeiten gehört sein Beitrag für die Bank of England1. Der von ihm entworfene Bauabschnitt blieb bis in die 1920er-Jahre in Betrieb und wurde dann abgerissen. Andere seiner Londoner Bauwerke kann man aber heute noch besichtigen, so etwa Pitzhanger Manor House, Moggerhanger Park und Wimpole Estate. Von 1806 bis zu seinem Tode lehrte Soane Architektur an der Royal Academy of Arts in London. Er war bekannt für seine sorgfältig vorbereiteten Vorlesungen und sein besonderes Interesse an der Architekturausbildung.

Auch wenn er schon während seiner Reisen durch Europa (1778-1780) – der obligatorischen Grand Tour – auf den Geschmack des Sammelns gekommen war (Münzen, Amphoren und noch größere Souvenirs gehörten zum guten Stil), wurde der eigentliche Funke für diese Leidenschaft erst mit seiner akademischen Karriere entfacht. Schon bald nach seiner Ernennung zum Architekturprofessor begann Soane – als Anschauungsmaterial für seine Schüler und Studenten – Antiquitäten, Bücher und Kunstwerke zu sammeln. Mitenthalten sind am Ende über 30.000 Architekturzeichnungen von renommierten Personen wie etwa James Gibbs, Christopher Wren, John Nash – und Sir John Soane selbst. 1.080 dieser Exemplare waren vorgesehen für die Vorlesungen der Royal Academy. Natürlich bewältigte Soane diese Leistung nicht allein. Für die Zeichenarbeit konnte er auf diverse Assistenten, Schüler oder Studenten zurückgreifen: das Sir John Soane’s Drawing Office2. Ein besonders wichtiger Zeichner und kreativer Partner von Soane war außerdem Joseph Michael Gandy. Die Sammlung beherbergte Soane schon zu seinen Lebzeiten in seinem Privathaus in London, das man nach seinem Tode 1837 zu einem Nationalmuseum erhob.

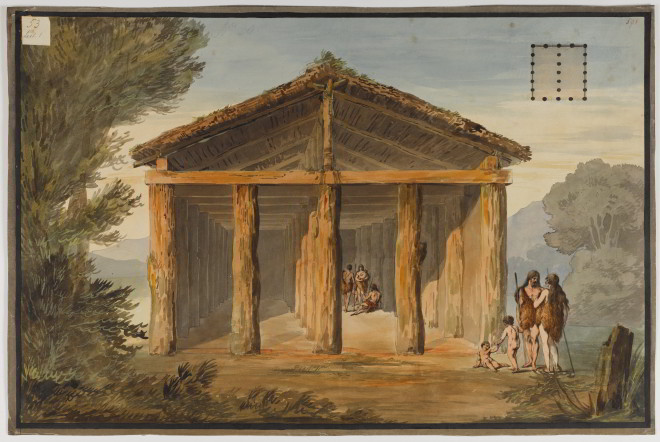

Für die Ausstellung Die klassischen Ordnungen: Mythos, Sinn und Schönheit in den Zeichnungen von Sir John Soane leiht das Sir John Soane‘s Museum 30 Blätter an die Tchoban Foundation in Berlin aus. Die Arbeiten basieren auf Techniken und Materialien wie Bleistift, Feder, Aquarell, farbige Lavierung und Büttenpapier. Viele von diesen herausragenden Stücken entstanden für Soanes akademische Arbeit. Mit ihrer Hilfe erklärte er seinen Studenten die klassischen architektonischen Ordnungen. Ohne die drei wichtigsten unter ihnen – dorisch, ionisch und korinthisch – begriffen zu haben, war für ihn die Ausübung der Architektur nicht denkbar. Die Tchoban Foundation gibt vom 22. September 2022 bis 15. Januar 2023 die Gelegenheit, diese von der Antike überlieferten Säulenordnungen so kennenzulernen, wie sie Soane per Zeichenkunst anpries. Die Ausstellung zeigt die Legenden über die Ursprünge der klassischen Ordnungen und wie sie der britische Architekt in seinem Werk nutzte.

In mindestens einem Punkt sind sich Ausstellungsthema und Ausstellungsort verwandt und das ist das Sammeln. Soane interessierte sich u. a. für Möbel, Skulpturen, Architekturfragmente und -modelle, Bücher, Zeichnungen und Gemälde, darunter Werke von Hogarth, Turner und Canaletto. Die Objekte, die er jahrzehntelang zusammenraffte, umspannen verschiedene Kontinente und mehrere Jahrtausende. Sergei Tchoban, Gründer der gleichnamigen Foundation (und selbst ein virtuoser Zeichner und ehemaliger „Papierarchitekt“), begann seine Sammlung mit einer Zeichnung von Pietro di Gottardo Gonzaga, die er 2001 erwerben konnte. (Der italienische Maler und Bühnenbildner gehörte seit 1792 zu den importierten Künstlern des russischen Hofs von St. Petersburg.) Seitdem ist die Sammlung des deutschen Architekten russischer Abstammung angewachsen; Blätter aus verschiedenen Epochen sind hinzugekommen. Tchoban besitzt Meisterzeichnungen, angefangen im 16. Jahrhundert bis hin zu Werken zeitgenössischer Architekten. Zu den Älteren gehören Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, Hubert Robert, Sir John Soane und Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Unter den Modernen befinden sich z. B. Frank Lloyd Wright und Lebbeus Woods.

Der Unterschied jedoch zwischen Soane und Tchoban liegt in ihrer Art, ihre Sammlung auszustellen. Soane bot seine in einem Komplex aus drei bestehenden Londoner Gebäude dar. (Das Erste davon kaufte er 1792, und da die ausufernde Sammlung mit der Zeit immer mehr Raum verlangte, kamen später die Nachbarhäuser dazu; das zweite folgte 1807 und das dritte 1823.) Die Adresse, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, liegt ganz in der Nähe des British Museum und hier wohnte er auch, inmitten seiner Schätze. (Und bei diesen Schätzen hat man den Eindruck, sie haben eine deutlich persönliche Note. Mehr noch, es kommt der Verdacht auf, der Bildungszweck der Sammlung ist doch nicht so „selbstlos“ gewesen. Sophie Thomas spricht bei diesem Hausmuseum sogar von einer „selbstreflexiven Konstruktion“ und nennt seinen Besitzer „Archivist des Selbst“3.) Soane bestückte und besetzte praktisch alles – neben den Fußböden jede Wand, jeden Pfeiler, jede Nische, jedes Möbel. Bis zu den Raumdecken und fast in die Lichtkuppeln hinein kann man Ausstellungsobjekte entdecken. Zu seinem überwältigenden Reichtum an Artefakten gehörte sogar ein ägyptischer Sarkophag. (Der Sarkophag von Seti I., 1817 von dem italienischen Entdecker Giovanni Battista Belzoni entdeckt, wurde – so wird erzählt – vom Britischen Museum als zu teuer abgelehnt, Sir John Soane aber griff zu.) Das Ambiente der Räume hat etwas von einem System aus Wohnhöhlen, manche Ecken erinnern an einen geheimen Hort. Die Räume sind überladen von Gegenständen; es weht ein Wind von einem ganzen Historien-Mix. (Dieser Hang, der auch seine Bauentwürfe auszeichnete, war nicht bei jedem beliebt. So etwa musste er 1824 viel Kritik und Spott über sich ergehen lassen, weil er seine Entwürfe mit Ornamenten überhäufen würde; ein satirischer Angriff auf ihn führte sogar zu einer erfolglosen Verleumdungsklage4.) Es ist nicht zu übersehen: Soane ging es in seiner Arbeit und Dauerausstellung oftmals darum, die Architektur der Vergangenheit und verschiedene Kulturen in einer bis zur Verwirrung grenzenden Mischung darzubieten und zu reflektieren. (Der Einsatz von Spiegeln in seinem Hausmuseum kommt auch deshalb wohl nicht von ungefähr.) Darüberhinaus betrachtete Soane die alten Stile als eine allumfassende Referenz, eine immerwährende Richtlinie, und das galt auch für die Bauwelt seiner Zeit.

Tchoban hingegen verleiht seiner Sammlungsstätte, dem Museum für Architekturzeichnung in Berlin, einen ganz anderen Rahmen. Er präsentiert die auserwählten Werke in einem zurückhaltenden Stil, die der Gegenwart verpflichtet ist. Die kaleidoskopische und verspielte, fast unaufgeräumte Atmosphäre von Soane wird bei Tchoban gesetzt und organisiert. Das Bauwerk, in dem seine Sammlung zu besichtigen ist, entstand 2013 in Berlin und wurde von Tchobans Moskauer Büro eigens für Ausstellungszwecke entworfen. Der Anblick der vier Geschosse erinnert an aufgestapelte Bauklötze oder Container. Ihre Fassaden aus Beton und Glas leben von Textur, Kontrasten und Schichten. So überraschen die sandsteinfarbenen Betonoberflächen durch eine besonders dezente Spezialität: Sie sind behandelt mit fräsenhaften Längsrillen, aber auch mit maximal vergrößerten Fragmenten architektonischer Skizzen in Reliefform. Diese abstrahierten dekorativen Muster der Betonoberflächen lassen ihre architektonischen Motive zuerst nur erahnen und liefern damit einen unaufdringlichen, versteckten Hinweis auf den Inhalt und die Funktion des Gebäudes. So signalisiert das Museum von Tchoban, dass es hier zwei Seiten zu entdecken gibt: Alt und Neu, das Traditionelle und Unorthodoxe, das Technische und Handwerkliche, die Vorlage und die Interpretation. Und beide Seiten können miteinander harmonieren und einander beleben.

Bei einer gefilmten Führung5 im Sir John Soane‘s Museum kann man dabei zusehen und zuhören, wie sich zwei der einflussreichsten Figuren der Architektur des 20. Jahrhunderts, Robert Venturi und Denise Scott Brown, im Haus von Soane umschauen. Robert Venturi, der zusammen mit seiner Partnerin die Funktionalität und den Purismus der Moderne anprangerte und der in den 60-iger Jahren für Komplexität und Widerspruch in der Architektur plädierte, ist begeistert. Was er hier erblickt ist eine durchgehende Idee: Es gibt ein Element und dahinter ein anderes Element und dahinter noch ein weiteres. Venturi und Scott Brown nannten es „Räumliche Schichtung“. Von diesem Spiel der Ebenen gehe ein Gefühl des Reichtums, der Widersprüche und Vielfalt aus. (Dinge, die die Moderne ausrottete). Der Anblick von Soanes Hausmuseum erinnert Venturi an Mies van der Rohe, den Modernisten und sein Motto „Less is more“ und daran, wie er selbst Mitte des Jahrhunderts als Postmodernist verkündete: „Less is a bore“.

Auch wenn Tchoban bekennt, dass die Moderne einiges verlernt hat6, zeigt er sich unabhängig von postmodernistischen Vereinnahmungen. Er versucht, Gegenwart und Vergangenheit zu verbinden, ohne Idealisierung oder Nachahmung, sondern mit Authentizität und auf Augenhöhe. Der Entwurf der Tchoban Foundation ist gebauter Ausdruck davon. Dennoch ist es bedeutungsvoll, dass er dieses Museum genau in jener Zeit gründete, als der digitale Entwurfsprozess die Architekturzeichnung zu verdrängen begann.

Sir John Soane – für den es nichts Ungewöhnliches war, mit Federkiel zu schreiben und zu zeichnen, und man darf annehmen, dass er dafür ein antiquarisches Modell bevorzugte – ist zum regelmäßigen Gast im Museum der Tchoban Foundation geworden, spätestens mit dieser vierten temporären Ausstellung. Die analogen Zeichnungen seines Studios beeindrucken mit feinsten Schattierungen und Details, mit dem lebendigen Spiel von Licht, von Hell und Dunkel, mit Farbpaletten von erdig bis strahlend. Die Arbeiten geben Einblick in Soanes Beziehung zu den antiken Baustilen und wie sie sich in seiner Praxis niederschlugen. Als zeitlose Inspirationen laden sie gleichzeitig dazu ein, sie zum eigenen Gewinn zu studieren, über die Geschichte der Architektur, ihre Stellung in der heutigen Baukultur, aber auch über Architekturausbildung nachzudenken. Die Präsentation ist, nicht zuletzt, ein erneutes Plädoyer für ein Revival der Handzeichnungen. Und: Sie ist garantiert nicht „langweilig“. ♦

¹ https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/museum/online-collections/archive-gallery/soane-bank; letzter Zugriff 7.9.2022

² https://www.soane.org/drawing-office; letzter Zugriff 7.9.2022. Das Zeichenbüro gehört zu den ältesten erhaltenen Beispielen eines architektonischen Zeichenbüros dieser Art und befindet sich direkt unter dem Dach des Sir John Soane Museums und kann ab Anfang 2023 besichtigt werden.

³ Siehe Sophie Thomas‘ Essay „A “strange and mixed assemblage”: Sir John Soane, Archivist of the Self” (https://muse.jhu.edu/article/739844/pdf; letzter Zugriff 7.9.2022).

⁴ http://www.berkshirehistory.com/bios/jsoane.html; letzter Zugriff 7.9.2022

⁵ https://www.britannica.com/video/164470/tour-documentary-London-Sir-John-Soanes-Museum; letzter Zugriff 7.9.2022

⁶ https://www.bauwelt.de/themen/Es-geht-um-den-aesthetischen-Genuss-Museum-fuer-Architekturzeichnung-Berlin-Sergei-Tchoban-Fassade-2102770.html; letzter Zugriff 7.9.2022

The Classical Orders: Myth, Meaning and Beauty in the Drawings of Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane, the master builder of the Regency and master draftsman, owned tens of thousands of architectural drawings. For the fourth time, the Tchoban Foundation in Berlin is offering a small glimpse into his magnificent art of analogue visualisation from 22 Sep 2022 to 15 Jan 2023.

Sir John Soane, a prolific builder and obsessive collector, is one of the most interesting figures in European architectural history. The son of a bricklayer, he was born in the county of Oxfordshire in 1753 and became a prominent architect of the British Regency era, even though his designs not infrequently remained unrealised. Within 50 years he worked on a wide range of extraordinary projects. One of his best-known works is his contribution to the Bank of England1. The section he designed remained in use until the 1920s when it was demolished. Yet you can still visit other of his London buildings today, such as Pitzhanger Manor House, Moggerhanger Park, and Wimpole Estate. From 1807 until his death Soane taught architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. He was known for his carefully prepared lectures and his particular interest in architectural education.

Even though he had already acquired a taste for collecting (coins, amphorae and even larger souvenirs were part of good style) during his travels through Europe (1778-1780) – the obligatory Grand Tour – the real spark for this passion came only with his academic career. Soon after his appointment as professor of architecture, Soane began collecting antiques, books and artworks – as illustrative material for his pupils and students. At the end, over 30,000 architectural drawings by renowned figures such as James Gibbs, Christopher Wren, John Nash – and Sir John Soane himself – were included. 1,080 of these exemplars were intended for the Royal Academy lectures. Of course, Soane did not manage this feat by himself. For the drawing work, he could call on various assistants, pupils or students: the Sir John Soane’s Drawing Office2. Furthermore, a particularly important draughtsman and creative partner of Soane was Joseph Michael Gandy. Soane hosted the collection during his lifetime in his private house in London, which was elevated to the status of a national museum after his death in 1837.

For the exhibition The Classical Orders: Myth, Meaning and Beauty in the Drawings of Sir John Soane, Sir John Soane’s Museum is now lending 30 sheets to the Tchoban Foundation in Berlin. The works employ techniques and materials such as pencil, pen and ink, watercolour, coloured wash and laid paper. Many of these outstanding pieces were created for Soane’s academic work. He used them to explain classical architectural orders to his students. For Soane, the practice of architecture was inconceivable without understanding the three most important of them – Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. From 22 September 2022 to 15 January 2023, the Tchoban Foundation will allow visitors to get to know these orders of columns, handed down from antiquity, the way Soane’s draughtsmanship extolled them. The exhibition reveals the legends about the origins of the classical orders and how the British architect drew on them in his work.

In at least one respect, the exhibition theme and the exhibition venue are related, and that is collecting. Soane’s interests included furniture, sculpture, architectural fragments and models, books, drawings and paintings, amongst them works by Hogarth, Turner and Canaletto. The objects he spent decades gathering span a variety of continents and several millennia. Sergei Tchoban, the founder of the eponymous foundation (and himself a virtuoso draughtsman and former „paper architect“), began his collection with a drawing by Pietro di Gottardo Gonzaga, which he was able to purchase in 2001. (The Italian painter and stage designer had been one of the imported artists of the Russian Court of St. Petersburg since 1792). Over the years, the collection of the German architect of Russian descent has grown; sheets from various epochs have been added. Tchoban owns master drawings, starting in the 16th century and extending to works by contemporary architects. Among the older ones are Jacques Androuet du Cerceau, Hubert Robert, Sir John Soane and Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Some of the Moderns are, for example, Frank Lloyd Wright and Lebbeus Woods.

The difference, however, between Soane and Tchoban lies in their way of displaying their collection. Soane presented his in a complex of three existing London buildings. (The first one he bought in 1792, and since the sprawling collection demanded more and more space over time, the neighbouring houses were added later on; the second followed in 1807, and the third in 1823.) The address, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, is very close to the British Museum and here he also lived, among his treasures. (And with these treasures, you get the impression they have a distinctly personal touch. Even more, the suspicion arises that the educational purpose of the collection was not so „selfless“ after all. Sophie Thomas goes so far as to speak of a „self-reflective construction“ in the case of this house museum and calls its owner an „Archivist of the Self“.3) Soane stocked and occupied practically everything – besides the floors, every wall, every pillar, every niche, every piece of furniture. One can discover exhibition objects up to the ceilings of the rooms and almost into the skylights. His overwhelming wealth of artefacts even included an Egyptian sarcophagus. (The sarcophagus of Seti I, discovered in 1817 by Italian explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni, was rejected – so the story goes – by the British Museum as too expensive, but Sir John Soane snapped at the chance). The ambience of the interior has something of a system of living caves, some corners evoke a secret hoard. The rooms are overloaded with objects; there is a wind of a whole mix of histories. (This tendency, which also characterized his building designs, was not popular with everyone. In 1824, for example, he had to endure much criticism and ridicule because he would clutter his designs with ornaments; a satirical attack on him even led to an unsuccessful libel suit4.) It cannot be overlooked: Soane’s work and permanent exhibitions were often about presenting and reflecting the architecture of the past and different cultures in a mélange that bordered on confusion. (His use of mirrors in his house museum is probably no accident for this reason, either). Soane regarded the old styles as an all-encompassing reference, a perpetual guideline, and this was true of the building world of his time as well.

Tchoban, on the other hand, gives his collection site, the Museum of Architectural Drawing in Berlin, a completely different setting. He displays the selected works in a low-key style that is committed to the present. Soane’s kaleidoscopic and playful, almost untidy atmosphere becomes sedate and organized in Tchoban’s museum. The building that houses his collection was built in Berlin in 2013 and was designed by Tchoban’s Moscow office specifically for exhibition purposes. The sight of the four stories is reminiscent of stacked building blocks or containers. Their facades of concrete and glass live from texture, contrasts and layers. The concrete surfaces in sandstone colour surprise with a particularly discreet speciality: they are treated with cutter-like longitudinal grooves, but also with maximally enlarged fragments of architectural sketches in relief form. These abstracted decorative patterns of the concrete surfaces, at first, only hint at their architectural motifs, thus providing an unobtrusive, hidden clue to the content and function of the building. In doing so, the Tchoban Museum signals that there are two sides to be discovered here: old and new, the traditional and the unorthodox, the technical and the artisanal, the model and the interpretation. And both sides can harmonize and enliven each other.

On a filmed guided tour5 at Sir John Soane’s Museum, you can watch and listen as two of the most influential figures of 20th-century architecture, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, look around Soane’s house. Robert Venturi, who, along with his partner, denounced the functionality and purism of modernism and who in the 1960s advocated complexity and contradiction in architecture, is thrilled. What he spots here is a continuous idea: there is one element, behind it a further one, and behind yet another. Venturi and Scott Brown called it „spatial layering.“ This play of levels, they said, emanates a sense of richness, contradictions and diversity. (Things that modernism eradicated). The sight of Soane’s house-museum reminds Venturi of Mies van der Rohe, the modernist, and his motto, „Less is more,“ and of how he himself, as a mid-century postmodernist, proclaimed, „Less is a bore.“

Even if Tchoban confesses that modernity has unlearned some things6, he shows himself independent of postmodernist appropriations. He tries to combine the present and the past without idealization or imitation, but with authenticity and at eye level. The design of the Tchoban Foundation is a built expression of this. Nevertheless, it is significant that he founded this museum precisely when the digital design process began to displace architectural drawing.

Sir John Soane – for whom it was nothing unusual to write and draw with a quill pen, and one may assume that he preferred an antiquarian model for this purpose – has become a regular guest at the Museum of the Tchoban Foundation, at the latest with this fourth temporary exhibition. The analogue drawings from his studio impress us with the finest shading and detail, the vivid play of light, luminosity and darkness, and colour palettes ranging from earthy to radiant. The works provide insight into Soane’s relationship with ancient architectural styles and how they were reflected in his practice. As timeless inspirations, they equally invite us to study them for our own benefit, to reflect on the history of architecture, its place in today’s building culture, and also on architectural education. The presentation is, not least, a renewed plea for a revival of hand drawings. And: it is definitely not „a bore“.

TRANSLATION BY ÖZLEM ÖZDEMIR

1 https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/museum/online-collections/archive-gallery/soane-bank; last access date 7.9.2022

2 https://www.soane.org/drawing-office; last access date 7.9.2022. The drawing office is one of the oldest surviving examples of an architectural drawing office of this type and is located directly under the roof of the Sir John Soane Museum and can be visited from the beginning of 2023.

3 See Sophie Thomas’s essay „A „strange and mixed assemblage“: Sir John Soane, Archivist of the Self” (https://muse.jhu.edu/article/739844/pdf; last access date 7.9.2022).

4 http://www.berkshirehistory.com/bios/jsoane.html; last access date 7.9.2022

5 https://www.britannica.com/video/164470/tour-documentary-London-Sir-John-Soanes-Museum; last access date 7.9.2022

6 https://www.bauwelt.de/themen/Es-geht-um-den-aesthetischen-Genuss-Museum-fuer-Architekturzeichnung-Berlin-Sergei-Tchoban-Fassade-2102770.html; last access date 7.9.2022