Die kubanisch-amerikanische Malerin Carmen Herrera starb Februar 2022, nur einige Monate nach der libanesisch-amerikanischen Malerin, Dichterin und Essayistin Etel Adnan. Beide Frauen haben ihren Platz in der Reihe der großen Kunstschaffenden gefunden.

28. Juli 2022 | Diana Page

D

ie Geschichte der Carmen Herrera ist inzwischen fast schon berüchtigt für ihren späten Ruhm. Wie sie selbst in dem Dokumentarfilm von Alison Klayman The 100 years show1 sagt: „If you wait for the bus, it will come.“ Etel Adnans Platz als bedeutende Künstlerin wurde in ihrem siebenundachtzigsten Jahr auf der Documenta 2012 in Kassel gewürdigt. Eine Erörterung der beiden Künstlerinnen bringt einige interessante Unterschiede und Gemeinsamkeiten zutage: Beide hielten sich nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg etwa zur gleichen Zeit in Paris auf und trafen die Künstler, Schriftsteller, Philosophen und Denker der Zeit. Etel Adnan studierte Philosophie an der Sorbonne und zog später in eine Wohnung in Paris zurück. Carmen Herrera lebte neunundvierzig Jahre lang in derselben Wohnung in der Nähe des Madison Square Park in New York. Beide führten ein Leben fern ihrer Heimat. Als Künstlerinnen haben ihre Werke eine Bedeutung, die über die nationale Identität, die Suche nach Anerkennung durch die Kunstwelt oder den Aufstieg zum Ruhm hinausgeht. Wie ein anderer amerikanischer Maler der 1950er-Jahre, Richard Diebenkorn2, schrieb: „If you don’t assume a rigid historical mission, you have infinitely more freedom.“ Sie starben im Abstand von einem Jahr: Sie starben im Abstand von einem Jahr, Carmen Herrera 2022 und Etel Adnan 2021.

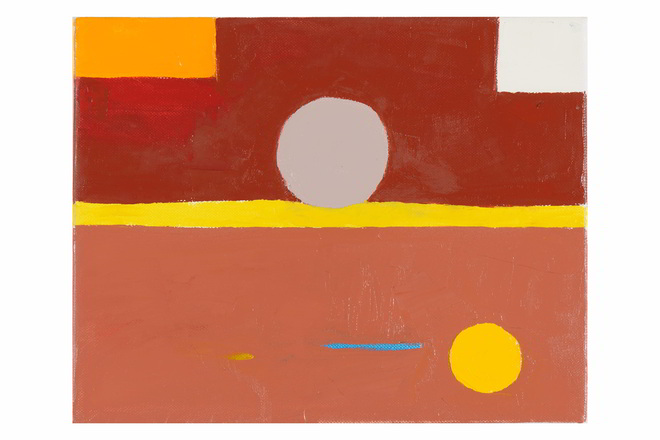

Beide Malerinnen haben etwas Ikonisches an sich, eine besondere Sprache, die sie begleitet, während sie die Welt durchstreifen und erkunden. Wenn man die Gemälde von Carmen Herrera betrachtet, denkt man unweigerlich an die gebaute Umwelt von New York, ihre Parks, Hochhäuser, Fenster, Feuerleitern und Wassertürme – das visuelle Wörterbuch der Orte, mit denen Carmen Herrera ihre Tage verbrachte. Etel Adnan, die für ihre Erforschung der Rhythmen der Natur bekannt ist, wie sie in Sonne, Meer, Bergen und Sternen zum Ausdruck kommen (siehe ihre farbenprächtigen Gemälde Untitled, 2010), fühlte sich ebenfalls von der Geometrie der New Yorker Skyline angezogen. Herrera kommentiert ihr eigenes Werk nicht auf eine so eng begrenzte Weise, sondern zieht es vor, es von jeder Diskussion über Ort und Zeit zu trennen. In seinem Essay im Katalog des Pera Museums für die Ausstellung Etel Adnan: Impossible Homecoming (2021) zitiert Hans Ulrich Obrist aus Carmen Herreras Notizbüchern: „Ultimately our real home is our life.“3

Ein besonderes Interesse beider Malerinnen gilt den Farben, ihren Nebeneinanderstellungen und der Art und Weise, wie sie den Raum auf einer Leinwand beeinflussen und gestalten. Beide arbeiteten mit bescheidenen Mitteln in ihren Wohnungen, an einem Tisch oder Schreibtisch sitzend, nicht an einer Staffelei in einem großen Atelier. Serhan Ada schildert in ihrem Essay Impossible Homecoming wie Adnan darauf hinweist, dass sie an einem Ende beginnt und am anderen herauskommt und dann ergänzt: „I wait for an airstream and then go with it…That’s an epiphany.“4 Bei Herrera findet sich die gleiche Haltung wieder. Auf die Frage, woran sie denkt, wenn sie ein Werk beginnt, antwortete sie: „the line, the paper…a lot of tiny things that get bigger and bigger.“5 Entscheidend für beide Künstlerinnen war das Zeichnen.

Als Malerin ist Adnans Antwort intuitiv und pittoresk. Ganz nach Hannah Arendts Definition von „poly- heimat“, gehörte sie vielen Ländern an. Sie arbeitete mit verschiedenen Medien, und ihre Werke sind nicht als separate, an der Wand befestigte Einheiten zu sehen, sondern eher als Gesamtkunstwerk. Als anerkannte Dichterin begann sie 1959 auf Anregung ihrer Lehrerin am UCL, Ann O’Hanlon, mit der Malerei. Als Tochter einer Griechin und eines osmanischen Soldaten wurde sie in Beirut geboren und hatte eine starke und faszinierende Persönlichkeit. Sie entschied sich, die nationalen Identitäten abzulegen und stattdessen in ihren Bildern die Gerüche, Sehenswürdigkeiten und Erfahrungen von Orten und Erinnerungen zu beschwören – Beirut und Smyrna, die 1922 zerstörte Geburtsstadt ihrer Mutter. Als sie 1955 nach Kalifornien zog, tauchte sie als selbst ernannte arabische Amerikanerin in neue „Lebensrhythmen“ ein, in das Meer, die Sonne und den Berg Tamalpais in Sausalito, der an die Berge ihres Geburtsortes erinnert. Wie Cezannes Gemälde des Mont Saint Victoire wurden diese Bilder von Etel Adnans Berg (z. B. Untitled, 2016) zu „Talismanen“, da sie den Berg immer wieder in verschiedenen Medien erkundete. Etel Adnans Formen sind weich, verschwommen, suggestiv – manchmal stellen sie Dinge und Orte dar oder rufen Ideen und Gefühle hervor. Etel Adnan legt großen Wert auf den menschlichen Abdruck in ihrer Zeichengebung.

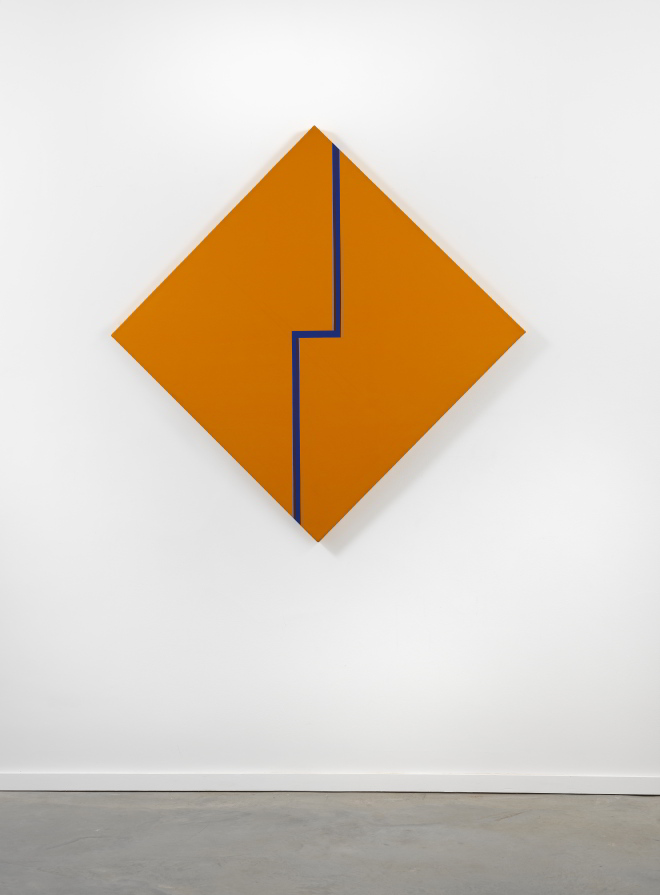

Carmen Herrera ist eine andere Art von Farbkünstlerin. Sie bezeichnet sich selbst als Hard-Edge-Malerin mit einem besonderen Interesse daran, wie Raum geschaffen und konfundiert werden kann, wenn eine Farbe neben eine andere gesetzt wird. Sie ist außerordentlich erfinderisch, und die Ergebnisse sind subtil in ihren Unvollkommenheiten, da sie genau darauf achtet, wie die Farben aneinanderstoßen und sich in späteren Arbeiten um den Rand der Leinwand falten oder über mehrere Leinwände hinweg bewegen. Die daraus resultierenden Arbeiten – Blue Angle on Orange (1982-83), worin Komplementärfarben als Linie, Richtung, Fläche und Ebene spannungsvoll gegeneinander ausgespielt werden – sind ein gutes Beispiel für den bildlichen Esprit und die zeichnerische Präzision. In ihrem Interesse am optischen Witz geht sie dem Werk einer anderen großen abstrakten Malerin, Bridget Riley, voraus.

Einige ihrer Affinitäten zu anderen Künstlern überschneiden sich, vor allem mit den Künstlern, die sich in der zweiten Hälfte des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts der Abstraktion zuwandten. In den Jahren 1948-1953 entstand eine spirituelle Qualität im Werk der frühen Abstraktionisten, Künstler der ungegenständlichen Kunst, die vielleicht angesichts der nationalsozialistischen Haltung, die die Kunst als „entartet“ bezeichnete, einen Platz für die Kunst suchten. Etel Adnan fühlte sich besonders zu Paul Klee hingezogen und sagte in Bezug auf ihn: „You forget that you are on this earth, you enter his forever.“6 Wie Klee und Kandinsky fühlte sich Adnan von der evokativen, fast musikalischen Kraft der Farbe angezogen. Durch die Farbe konnte sie eine kraftvolle Entsprechung zu ihrer Erfahrung der Welt, ihrer „Vision der Welt“, schaffen.

In Paris, so Carmen Herrera, verliebte sie sich in Europa7 und fand ihr eigenes bildnerisches Vokabular. Frankreich war fortschrittlicher als das Amerika der 1940er-Jahre. In Paris lebten sie und ihr Mann Jesse Loewenthal am linken Ufer in Montparnasse und freundeten sich mit vielen Künstlern und Schriftstellern an. Herrera interessierte sich für die Werke von Mondrian, Matisse und Picasso, wobei sie Matisse als Mensch bevorzugte. Mit Letzterem verbindet sie eine Verwandtschaft, denn sie zeichnet, misst, misst nach, radiert, schneidet und klebt, zunächst mit Bleistift, Filzstift und Papier, bevor sie zu ihren großen Leinwänden übergeht. Sie vergleicht ihren Assistenten Manuel Belduma mit Matisse‘ Nonnen im Krankenhaus, die ihm in seinen letzten Jahren bei seinen Scherenschnitten halfen. Die „Tänzerinnen“ von Matisse, bei denen eine Kurve auf eine gerade Linie trifft, werden in Dia Feriado (2011) in Erinnerung gerufen.

In Paris stellte Herrera zusammen mit anderen Künstlern aus, die sich mit Farbe und Abstraktion beschäftigten, darunter Josef Albers, Jean Arp, Sonia Delauney, Kasimir Malewitsch und die frühen russischen Suprematisten. Sie war auch mit dem Maler des Abstrakten Expressionismus Barnett Newman befreundet. Ihre Arbeiten stehen sich in der Tat nahe und teilen eine monumentale geometrische Einfachheit, wie in Verticals #2 (1989) zu sehen ist, obwohl sie sich auch hier durch malerischen Witz auszeichnen, da der Raum zweideutig und spielerisch gestaltet ist. Während Barnett Newman seine Intentionen mit Spiritualität verband, zog es Herrera vor, dies nicht zu tun.

Als Herrera in den 1950er-Jahren nach New York zurückkehrte, fand sie nicht die Anerkennung, die sie verdiente. In Klaymans Dokumentarfilm erinnert sie sich an einen Besuch bei einer prominenten Galeristin, Rose Fried, die ihr später am Telefon erklärte: „… you know, Carmen, you can paint rings around the men artists I have, but I’m not going to give you a show because you’re a woman.“ Herrera bemerkt dazu: „I felt as if someone had slapped me on the face. I felt for the first time what discrimination was. It’s a terrible thing. I just walked out.“8

Sie wurde auch nicht in die Ausstellung 16 Americans im Jahr 1959 aufgenommen, in der die bekannten abstrakten Maler der 1950er-Jahre vertreten waren, wie der berühmte Hard-Edge-Maler Ellsworth Kelly. Heute hängt ihr Werk, zu Recht, zusammen mit seinem im Whitney Museum. Aber zu jener Zeit war sie als kubanische Malerin einfach „nicht sichtbar“. Sie glaubte zudem, dass die Auseinandersetzung mit geometrischer Abstraktion und Hard-Edge-Malerei als etwas angesehen wurde, das für eine Malerin nicht akzeptabel war. Aber letztendlich schätzte sie diesen Freiraum. In einem Interview aus dem Jahr 2010, das vor einer früheren Ausstellung in der Lisson Gallery stattfand, sagte Herrera zu Hermoine Hoby9 vom Observer: „When you’re known you want to do the same thing again to please people. And, as nobody wanted what I did, I was pleasing myself, and that’s the answer.“

Herrera hielt sich an das Diktum „less is more“. Es ist aufschlussreich, frühere Gemälde wie Green Garden (1950) und Iberic (1949) zu betrachten, in denen die Formen einer Stadtlandschaft oder eines Stadtparks anklingen, und dann spätere Werke, in denen die Lineamente einer Landschaft in einer neuen Art von formaler Konstruktion zusammengefasst werden. In diesen Werken werden ihre Erkundungen mit geraden Linien, Kurven, Dreiecken und farbigen geometrischen Formen, die sich aneinanderreihen, rein formal. Die außergewöhnliche Präzision und Subtilität ihrer Arbeit zeigt sich in Kompositionen, die auf innovative Weise ein Gleichgewicht herstellen – ihre eigene Bildsprache. Die Linien berühren sich nicht wie in The Way (1970) oder reichen nicht bis zum Rand der Leinwand. Die Asymmetrie der Kompositionen schafft überraschende Ausrichtungen oder Nichtausrichtungen. Ihre Prägnanz als Malerin und die Straffheit ihrer Komposition erreichen ihren Höhepunkt in Blanco Y Verde (1959), wo der Raum der Bildebene sparsam und pfeilartig von einem abgeflachten grünen Dreieck durchstoßen wird. Es handelt sich um eine Art visuelle Poesie, die Holland Cotter in der ersten Presseberichterstattung über Herrera, einer kurzen Besprechung einer kleinen Ausstellung in einer Galerie in East Harlem, die der lateinamerikanischen Kunst gewidmet war, dazu veranlasste, sie als „eine abstrakte Kunst mit leise jazzigen linearen Mustern“10 zu beschreiben.

Gemeinsam ist Herrera und Adnan die Liebe zur Architektur. Als abstrakte Malerinnen betrachteten sie ein Gemälde als etwas Konstruiertes, das seine eigene Sprache hat. Adnan wollte Architektin werden; Herrera studierte während der turbulenten Jahre der kubanischen Revolution für kurze Zeit Architektur. Es war eine prägende Zeit, von der sie sagt: „There, an extraordinary world opened up to me that never closed: the world of straight lines, which has interested me until this very day.“11 Vielleicht war „die Schönheit der geraden Linie“ ein Gegenmittel gegen die Turbulenzen, die sie um sich herum erlebte. In The 100 Year Show erinnert sich Herrera an ihr Leben in Havanna und an die Erfahrung, wie die Hoffnung des kubanischen Volkes auf die Revolution durch eine Diktatur erstickt wurde.

Im Œuvre beider Künstlerinnen finden wir Bilder, die über den Rahmen, die Leinwand oder das Stück Papier hinauswachsen wollen. Herreras Gemini (Red) (1971/2019) und Amarillo Uno (1971) sind gute Beispiele dafür. Beide Künstlerinnen waren sich der Bedeutung öffentlicher Kunstwerke bewusst, die dem Kunstwerk nicht nur Raum für die Interaktion mit der gebauten Umwelt bieten, sondern auch Menschen in dieser Umgebung zusammenbringen. Kunst im öffentlichen Raum behauptete somit eine Gemeinschaftlichkeit, die es ermöglichte, die Unterschiede von Sprache, Kultur und Rasse zu überwinden. Herrera und Adnan teilten den Wunsch, ein künstlerisches Werk zu schaffen, das in seiner apriorischen Form nicht in unseren zahlreichen Vorurteilen über das Sehen und Verstehen der Welt verwurzelt ist.

Carmen Herrera träumte davon, ihre zunehmend skulpturalen Gemälde in die Landschaft zu bringen. Ihr Traum wurde schließlich in Estructuras Monumentales (2019) im vom Public Art Fund verwirklicht. Hier bevölkerten ihre gemalten dreidimensionalen geometrischen Formen endlich die urbane Landschaft, boten Objekte der Schönheit und hoben die Stimmung der Passanten. Die Installation reiste anschließend in den Buffalo Bayou Park, Houston, USA. Etel Adnan, die auch Schriftstellerin und Dichterin war, griff die Form des japanischen „Leporellos“ auf (ein ausdehnbares Ziehharmonika-Skizzenbuch: siehe Untitled, 1965), das sie mit sich führen konnte. Mit fortschreitendem Leben vereinte es Wort und Bild, die Zeichen der Sprache und die Zeichen der Zeichnung. Durch diese Arbeiten entfaltet sich das Gedankliche selbst. Sie schuf auch zahlreiche Wandteppiche und Keramikflieseninstallationen, die öffentlich ausgestellt wurden.

Die Architektur der britisch-irakischen Architektin Zaha Hadid wurde von Etel Adnan beschrieben als Poesie, eine Spiritualität, die uns beschützt, uns träumen lässt und uns auf eine Reise schickt.12 Die Bildhauerin Simone Fattal, die 47 Jahre lang die Lebensgefährtin von Etel Adnan war, beschrieb ihre Bilder als reine Energie, mit der man sein Leben mutig leben kann13. Carmen Herrera sagte dem W Magazine14 vor ihrem 100. Geburtstag: „Life is wonderful and funny… and then you get to be 100.“ Gefragt von Simon Hattenstone15 vom Guardian, ob sie Emotionen in ihren Gemälden sähe und ob sie Bilder der Liebe wären, antwortete sie mit „Ja“.

Etel Adnan war der Ansicht, dass Architektur alles enthält: Form, Farbe und soziale Belange16. Vielleicht spiegelt das Werk dieser zwei Künstlerinnen – in ihren Konstruktionen einer Sprache der Schönheit – Carmen Herreras Bestreben wider, etwas Ordnung in das Chaos zu bringen, in dem wir leben, und bietet eine Art Schutz für die Künstlerin und dann für den Betrachter oder Passanten. ♦

(Übersetzung aus dem Englischen: Özlem Özdemir)

¹ https://alisonklayman.com/the-100-years-show; last access date 1.7.2022

² https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/richard-diebenkorns-artistic-evolution-a-brave-statement-of-independence; last access date 1.7.2022

³ “Ever Etel”, (Essay in Exhibition Catalogue: Impossible Homecoming, Pera Müzesi, April 2021) Hans Ulrich Obrist, S.45

⁴ Etel Adnan, Impossible Homecoming (Exhibition Catalogue), Pera Muzesi, April 2021. Edited by Ada Serhan, S.31

⁵ ebd.:1

⁶ “Ever Etel”, (Essay in Exhibition Catalogue: Impossible Homecoming, Pera Müzesi, April 2021) Hans Ulrich Obrist, S.53

⁷ ebd.:1

⁸ ebd.:1

⁹ https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2010/nov/21/carmen-herrera-artist-interview; last access date 1.7.2022

¹⁰ https://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/24/arts/art-in-review-carmen-herrera.html; last access date 1.7.2022

¹¹ Miller, Dana (2016). „Carmen Herrera: Sometimes I Win“ (Exhibition catalogue Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight). Whitney Museum of American Art, S. 15

¹² “Ever Etel”, (Essay in Exhibition Catalogue: Impossible Homecoming, Pera Müzesi, April 2021) Hans Ulrich Obrist, S.49

¹³ ebd.:3

14 https://www.wmagazine.com/story/carmen-herrera-artist-99-years-old; last access date 1.7.2022

15 https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/dec/31/carmen-herrera-men-controlled-everything-art; last access date 1.7.2022

16 “Ever Etel”, (Essay in Exhibition Catalogue: Impossible Homecoming, Pera Müzesi, April 2021) Hans Ulrich Obrist, S.51

DIANA PAGE

Diana Page ist eine Malerin, die in Istanbul lebt. Sie ist in Südafrika geboren und aufgewachsen. Ihre Arbeiten in den Bereichen Malerei, Zeichnung und Multi-Media zeugen von ihrem Interesse an flüchtigen urbanen Momenten und Räumen als auch an Themen wie Erinnerung und Migration.

Carmen Herrera and Etel Adnan – Painting substance into subtlety

Cuban-American painter Carmen Herrera died in February 2022, just a few months after Lebanese-American painter, poet and essayist Etel Adnan. Both women have found their place within the panoply of great artists.

Carmen Herrera’s story is almost infamous by now for her late arrival to fame. As she herself says in the documentary by Alison Klayman The 100 years show1: „If you wait for the bus, it will come“. Etel Adnan’s place as an artist of importance was recognized in her eighty-seventh year at the 2012 Documenta, Kassel. A discussion of the two artists throws up some interesting differences and similarities: Both enjoyed significant sojourns in Paris around the same time after the Second World War, meeting the artists, writers, philosophers and thinkers of the time. Etel Adnan studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and later on in her life moved back to an apartment in Paris. Carmen Herrera lived in the same apartment near Madison Square Park, New York, for forty-nine years. Both lived lives away from their homeland. As artists, their work has a significance that goes beyond national identity, a search for recognition by the art world or a rise to fame. As another American painter of the 1950s, Richard Diebenkorn2 wrote, “If you don’t assume a rigid historical mission, you have infinitely more freedom.” They died one year apart, Carmen Herrera in 2022, and Etel Adnan in 2021.

There is something iconic about both painters, a creation of a particular language that accompanies them as they navigate and explore the world. One cannot help looking at the paintings of Carmen Herrera and thinking of the built environment of New York, its parks, high rises, windows, fire escapes, and water towers – the visual dictionary of where Carmen Herrera spent her days. Etel Adnan, while known for her exploration of the rhythms of nature as expressed in sun, sea, mountain and stars (as illustrated in the vividly coloured paintings Untitled 2010), was also drawn to the geometry of the New York skyline. Herrera offers no such localised comment on her own work, preferring to keep it separate from any discussion of place or time. Hans Ulrich Obrist’s essay in the Pera Museum catalogue for the 2021 exhibition, Etel Adnan: Impossible Homecoming, extracts from Carmen Herrera’s notebooks: “Ultimately our real home is our life.”3

Both painters are intensely interested in colour, its juxtaposition, and how it affects and creates space across a canvas. Both worked with modest means in their homes, seated at a table or desk, not working on an easel in a vast studio. Serhan Ada, in her essay Impossible Homecoming, describes Adnan as having pointed out that she starts at one end and comes out at the other and then adds to it: „I wait for an airstream and then go with it…That’s an epiphany.“4 Herrera echoes this approach. When asked what she thinks about when she starts a work, she replied, „the line, the paper…a lot of tiny things that get bigger and bigger.“5 For both artists, drawing was key.

As a painter, Adnan’s response is intuitive and painterly. According to Hannah Arendt’s definition, she was a “poly-heimat” belonging to many countries. She worked across multiple media, and her works are not to be seen as separate, wall-mounted entities but rather as gesamtkunstwerk. Already a recognized poet, she embarked on her work in painting in 1959 under the encouragement of a teacher at UCL, Ann O’Hanlon. Born in Beirut to a Greek mother and an Ottoman military father, she had a strong and compelling identity. She chose to cast off these national identities, instead allowing her paintings to conjure the smells, sights and experiences of place and memory – Beirut and Smyrna, her mother’s birthplace, destroyed in 1922. She moved to California in 1955, as a self-proclaimed Arab American, immersing herself in new “rhythms of life”, the sea, the sun and the Tamalpais Mountain of Sausalito, which recalled the mountains of her birthplace. Like Cezanne’s paintings of Mont Saint Victoire, these images of Etel Adnan’s mountain (Untitled, 2016, for example) became “talismanic”, as she explored the mountain over and over in a variety of media. Etel Adnan’s forms are soft, blurred, suggestive – sometimes depicting things and places or evoking ideas and feelings. Etel Adnan values the human print in her mark-making.

Carmen Herrera is a different kind of colourist. She calls herself a hard-edge painter with a specific interest in how space may be created and confounded, as one colour is placed next to another. She is extraordinarily inventive, and the results are subtle in their imperfections as she attends precisely to how colour abuts and, in later work, folds around the edge of the canvas or moves across multiple canvases. The resulting works – Blue Angle on Orange (1982-83) where the two complementary colours are tautly pitted against each other as line, direction, surface and plane, is a fine example – having both a pictorial wit and a precision of drawing. In her interest in optical wit, she precedes the work of another great woman abstract painter, Bridget Riley.

Some of their affinities with other artists overlap, especially with those artists who journeyed towards abstraction during the second half of the twentieth century. 1948-1953 saw a spiritual quality emerge in the work of the early abstractionists, artists of non-objective art who perhaps sought a place for art in the face of Nazi attitudes that labelled art as “degenerate”. Etel Adnan was particularly drawn to Paul Klee, saying of the painter: “You forget that you are on this earth, you enter his forever.“6 Adnan, like Klee and Kandinsky, was drawn to the evocative, near musical power of colour. Through colour she was able to create a powerful equivalent to her experience of the world, her „vision of the world“.

In Paris, Carmen Herrera said, “she fell for Europe”7 and found her own pictorial vocabulary. France was more progressive than 1940s America. In Paris, she and her husband Jesse Loewenthal lived on the Left Bank in Montparnasse, befriending many artists and writers. Herrera gravitated towards the works of Mondrian, Matisse and Picasso, preferring Matisse as a human being. With the latter, she shares a kinship as she draws, measures, re-measures, erases, cuts and tapes, first with pencil, felt pen and paper, before moving onto her large canvases. She compares her assistant Manuel Belduma to Matisse’s nuns in the hospital as they assisted him with his paper cut-outs in his later years. Matisse’s “Dancers”, where a curve bounds to meet the straight line, is called to mind in Dia Feriado (2011).

In Paris, Herrera exhibited alongside other artists exploring colour and abstraction, including Josef Albers, Jean Arp, Sonia Delauney, Kasimir Malevich, and the early Russian Suprematists. She was also a friend of the Abstract Expressionist painter Barnett Newman. Indeed, their work has an affinity and shares a monumental geometric simplicity, as seen in Verticals #2 (1989), although again, here distinguished by a pictorial wit as space is made ambiguous and playful. While Barnett Newman attributed spirituality to his intentions, Herrera preferred not to do so.

Returning to New York in the 1950s, Herrera failed to garner the recognition she deserved. In Klayman’s documentary, she recalls visiting a prominent gallerist, Rose Fried, who called back saying, “… you know, Carmen, you can paint rings around the men artists I have, but I’m not going to give you a show because you’re a woman.” Herrera remarks on this: ”I felt as if someone had slapped me on the face. I felt for the first time what discrimination was. It’s a terrible thing. I just walked out.”8

She was also not included in the 1959 exhibition 16 Americans, which featured the well-known abstract painters of the 1950s, such as the famous hard-edge painter Ellsworth Kelly. Today, her work hangs, rightly, with his at the Whitney Museum. But at the time, as a Cuban painter, she was simply „not visible.“ She also believed that tackling geometric abstraction and hard edge painting was seen as something not acceptable for a woman painter. But ultimately, she cherished this space of freedom. In a 2010 interview before a previous exhibition at Lisson Gallery, Herrera told Hermoine Hoby9at the Observer: “When you’re known you want to do the same thing again to please people. And, as nobody wanted what I did, I was pleasing myself, and that’s the answer.”

Herrera held by the dictum “less is more”. It is informative to look at earlier paintings like Green Garden (1950) and Iberic (1949) as they echo the forms of urban landscape or a city park, and then later works where the lineaments of any landscape are subsumed into a new kind of formal construction. In these, her explorations with straight lines, curves, triangles and coloured geometric forms edging against each other become more purely formal. The extraordinary precision and subtlety of her work reveals itself in compositions where balance is attained in innovative ways – her own pictorial language. Lines do not touch as in The Way (1970), or do not reach the edge of the canvas. The asymmetry of the compositions creates surprising alignments or non-alignments. Her concision as a painter and the tautness of her composition reach their peak in Blanco Y Verde (1959), where the space of the picture plane is pierced sparingly and arrow-like by a flattened green triangle. This is a kind of visual poetry that led Holland Cotter, in the first press coverage of Herrera, a short review of a small exhibition in a gallery in East Harlem dedicated to Latin American art, to describe it as “an abstract art of quietly jazzy linear patterns“10.

Herrera and Adnan share a love of architecture. As abstract painters, they viewed a painting as a constructed thing, with its own language. Adnan wanted to be an architect; Herrera studied architecture for a short time during the turbulent years of the Cuban revolution. It was a formative time of which she said: “There, an extraordinary world opened up to me that never closed: the world of straight lines, which has interested me until this very day.“11 Perhaps “the beauty of the straight line” was an antidote to the turbulence she was experiencing all around her. In The 100 Year Show Herrera recalls her life in Havana and the experience of watching the Cuban people’s hope in the revolution being stifled by a dictatorship.

In the œuvre of both artists, we find images wanting to expand beyond the frame, canvas or piece of paper. Herrera’s Gemini (Red) (2019) and Amarillo Uno (1971) exemplify this. Both artists understood the importance of public artworks that provided space for the piece of art, not only to interact with the built environment but to bring together people within these environments. Art in public space thus asserted a commonality that allowed it to transcend distinctions of language, culture and race. Herrera and Adnan shared the desire to create artwork that, in its apriori forms, is somehow not rooted in our various preconceptions of seeing and understanding the world.

Carmen Herrera dreamt of taking her increasingly sculptural paintings into the landscape. Her dream was finally realized in Estructuras Monumentales (2019) in City Hall Park by Public Art Fund. Here her painted three-dimensional geometric forms at last inhabited the urban landscape, offering objects of beauty and lifting the spirits of the passerby. The installation then travelled to Buffalo Bayou Park, Houston, USA. Etel Adnan, who was also a writer and a poet, adopted the form of the Japanese “Leporello” (an expanding concertina sketchbook: see Untitled, 1965), which she could carry with her growing alongside life itself, incorporating word and image, the signs of language, and the signs of drawing. Thought itself unfolds through these works. She also produced numerous wall tapestries and ceramic tile installations that were publicly displayed.

The British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid’s architecture has been described by Etel Adnan „as poetry, a spirituality, such that in sheltering us, it makes us dream, it sets us off on a journey“12. Sculptor Simone Fattal, and Etel Adnan’s partner of 47 years, described her paintings “as pure energy with which to live one’s life with courage“13 (Obrist,45). Carmen Herrera famously said to W Magazine14 before her 100th birthday, “Life is wonderful and funny… and then you get to be 100”. In an interview with Simon Hattenstone15 of the Guardian, when asked “Does she see emotion in her paintings? “Yes,” she says. Are they images of love? “Yes.””

Etel Adnan believed that “Architecture contains everything, form, colour, social concerns.“16 (Obrist,51) Perhaps the work of this two artists – in their construction of a language of beauty – echoes Carmen Herrera’s quest “to bring some order into the chaos that we live in”, providing a kind of shelter to the artist, and then to the viewer or passerby.

1 https://alisonklayman.com/the-100-years-show; last access date 19.7.2022

2 https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/richard-diebenkorns-artistic-evolution-a-brave-statement-of-independence; last access date 19.7.2022

3 “Ever Etel”, (Essay in Exhibition Catalogue: Impossible Homecoming, Pera Müzesi, April 2021) Hans Ulrich Obrist, p.45

4 Etel Adnan, Impossible Homecoming (Exhibition Catalogue), Pera Muzesi, April 2021. Edited by Ada Serhan, p.31

5 ibid.:1

6 “Ever Etel”, (Essay in Exhibition Catalogue: Impossible Homecoming, Pera Müzesi, April 2021) Hans Ulrich Obrist, p.53

7 ibid.:1

8 ibid.:1

9 https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2010/nov/21/carmen-herrera-artist-interview; last access date 19.7.2022

10 https://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/24/arts/art-in-review-carmen-herrera.html; last access date 19.7.2022

11 Miller, Dana (2016). „Carmen Herrera: Sometimes I Win“ (Exhibition catalogue Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight). Whitney Museum of American Art, p. 15

12 “Ever Etel”, (Essay in Exhibition Catalogue: Impossible Homecoming, Pera Müzesi, April 2021) Hans Ulrich Obrist, p.49

13 ibid.:3

14 https://www.wmagazine.com/story/carmen-herrera-artist-99-years-old; last access date 19.7.2022

15 https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/dec/31/carmen-herrera-men-controlled-everything-art; last access date 19.7.2022

16 “Ever Etel”, (Essay in Exhibition Catalogue: Impossible Homecoming, Pera Müzesi, April 2021) Hans Ulrich Obrist, p.51

DIANA PAGE

Diana Page is a painter living in Istanbul, Turkey. Born and raised in South Africa, her work in painting, drawing and multi-media conveys an interest in fleeting urban moments and spaces, memory and migrancy.