Chybik+Kristof macht mehr aus einer Mehrzweckarena. Ihr Wettbewerbsentwurf für ein Eishockeystadion in Jihlava ersetzt einen Vorgängerbau aus den 50er Jahren. Unweit des größten Platzes der tschechischen Stadt gibt das neue Projekt den Startschuss: Vorhang auf für eine urbane Stätte mit Campus-Atmosphäre und Sinn für regionale Identität.

19. Juli 2020 | Özlem Özdemir

D

as Repertoire von Chybik+Kristof Architects & Urban Designers wächst seit ihrer Bürogründung in 2010 unaufhörlich an. Von Wohnbau bis Weinkeller beherrschen sie diverse Typologien. Ihre Produktivität grenzt an Sportlichkeit. Umso passender ist ihr neuester Auftrag für ein Eishockeystadion, das 2023 nach nur zwei Jahren Bauzeit enden soll. Ihr jüngst gewonnener Wettbewerb verleiht eines der größten Sport- und Freizeitkomplexe in der Tschechischen Republik, der Mehrzweckarena Jihlava, eine neue Gestalt.

Jihlava? Das ehemalige Iglau liegt fast auf halber Strecke zwischen Prag und Brünn. Mit seinen rund 50.000 Einwohnern scheint es ein Ort zu sein, der etwas am Rande geblieben ist. Dennoch hat er bemerkenswerte und bewegende Hintergründe aufzuweisen.

Jahr 1968: Truppen des Warschauer Pakts marschieren in die Tschechoslowakei ein. Evžen Plocek zündet sich im Jahr darauf aus Protest gegen die sowjetische Aggression in Brand. Der Selbstmord geschieht mitten in der Stadt, auf dem Hauptplatz Masarykovo namesti. Der Werkzeugmacher ist nur einer von mehreren lebenden Fackeln. Zeitsprung, gleiche Stelle: Seit den 80er Jahren bildet ein länglicher Bau, ein Meteroit mit eingebautem McDonald, das Zentrum der Stadt. Das Wort ‚deplatziert‘ bekommt absofort eine anschauliche Darstellung. Hat das schwarz-weiße, fast stillose und umstrittene Kaufhaus Prior aus sozialistischen Zeiten doch nichts zu tun mit den Bauwerken unterschiedlichster Epochen (bis hin zur Gotik), die den Platz säumen. Ein paar Schritte weiter und fast zwei Jahrhunderte zurück: Dicht am südlichen Ende des Masaryk-Platzes, steht das Haus, in dem Gustav Mahler seine Kindheit verbracht hat. Der Komponist gilt als Wegbereiter der Moderne in der Musik, so wie sein Zeitgenosse Walter Gropius, Gründer des Bauhauses, der zu einer wichtigen Figur für die Moderne der Architektur avancierte1.

Das ist ein passendes Sprungbrett zum eigentlichen Thema. Quasi gegenüber des Mahler-Hauses, über den Platz hinweg mit seinem Gemisch aus historischen Gebäuden und liebloser Architektur der Gegenwart und Schauplatz erschreckender Vorfälle der jüngeren Geschichte, soll nun endlich eine Architektur entstehen, die den Geist der Moderne nach Jihlava bringen soll.

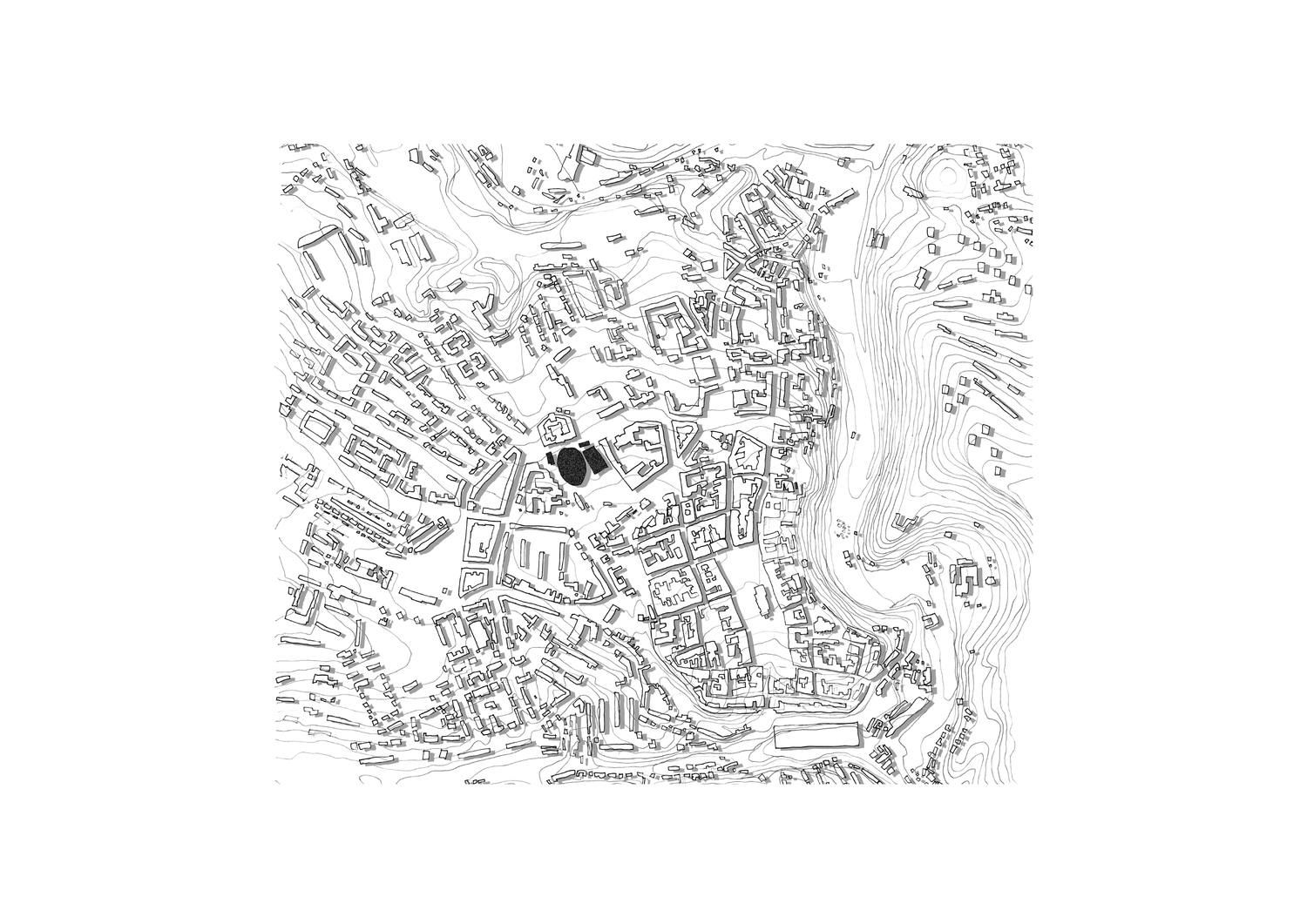

Wie aber sah der bisherige Sport- und Freizeitkomplex der Stadt aus? Was soll das Wettbewerbsprojekt von Chybik+Kristof ersetzen? Die Standortbesichtigung (via Googlemaps) präsentiert ein Gebäude, dessen wichtigstes Charakteristikum darin zu bestehen scheint, sich breitzumachen. Es zwängt sich zwischen die Polytechnische Hochschule Jihlava (die an die Randzone der Stadt grenzt) und dem altstadtnahen Smetana-Park. Seit den 50er-Jahren dient der Bau als Eishockeystadion. Zusammen mit einem unterirdischen Parkhaus besetzt er die ganze Parzelle. Hier endet aber schon die Übersichtlichkeit. Der Baukörper macht einen zusammengeflickten Eindruck. Die Wände sind zum Teil aus Ziegel, manche Bereiche sind in Ocker und Bordeaux-Rot getüncht (die Vereinsfarben). Und seine gesamte Seitenfront, die sich zum Park öffnet, ist verglast. Der alte Komplex wirkt von oben kompakt und doch verrät seine aufgebrochene, gestückelte Dachlandschaft unterschiedliche Raumzonen. Hier und da verbirgt sich hinter der konfusen Hülle außerdem noch ein Laden für Hockey-Bedarf und ein Kosmetikgeschäft. Ferner befindet sich in einem Eckbau eine Bierstube, die obligatorische Vereinskneipe. Es ist unschwer zu erkennen: Die Ausgangsbedingung der neuen Jihlava Mehrzweckarena war verwirrend.

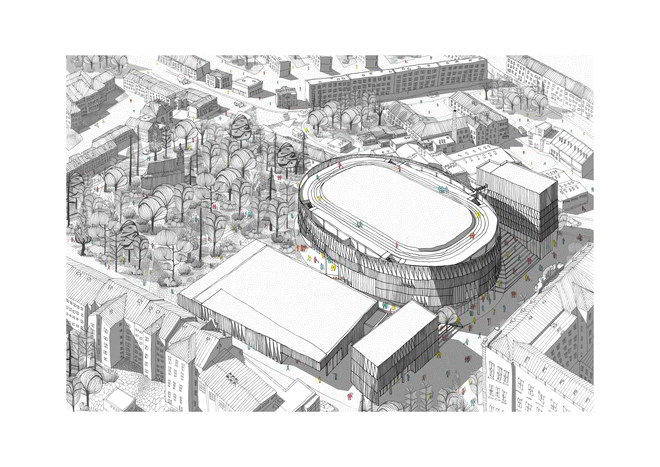

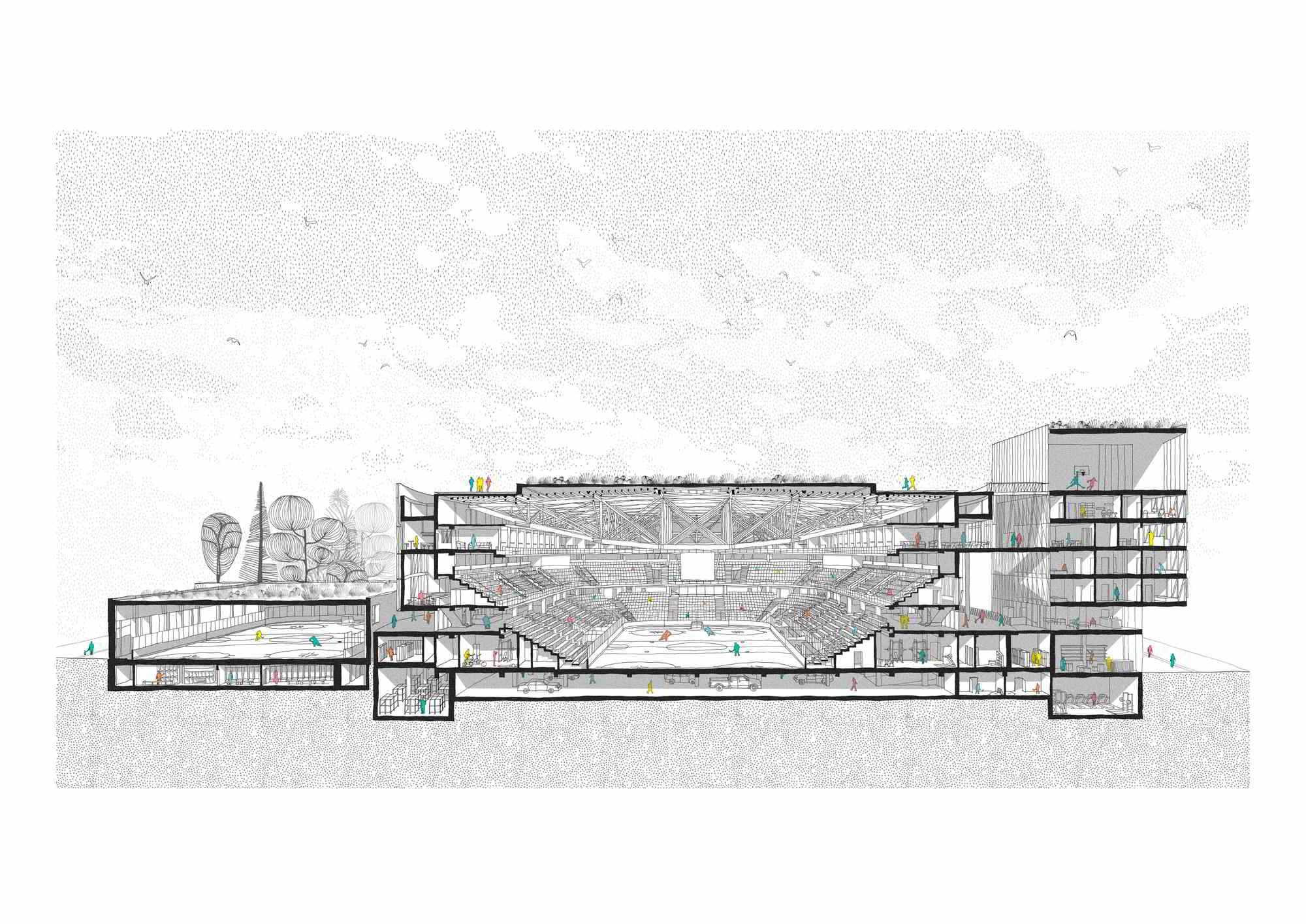

Chybik+Kristof lassen aus dem amalgamartigen Vorgänger vier getrennte Gebäude herauskristallisieren und ermöglichen dadurch Ordnung und Komposition. Drei von ihnen (die z. T. auf dem Bestand basieren) stecken gleichsam die Ecken ab. Damit verhelfen sie zu einem Rahmen für das Herz der dezentralen Anlage: eine großzügige neue Arena, ein monumentales Bauwerk für 5600 Zuschauer. Dieser ovale Hallenbau ist vielseitig nutzbar. Sein Innenraum fungiert als Eishockey-Bahn, Ausstellungs- und Veranstaltungshalle sowie als Konzertort. Seine Flexibilität erweitert sich noch durch eine Turnhalle. Und es gibt sogar ein Sahnehäubchen, passenderweise auf dem Dach: Hier ruht eine Außenbahn, die das sportive Angebot des Gebäudes bereichert und der Bevölkerung einen freien Ausblick auf ihre Stadt bietet.

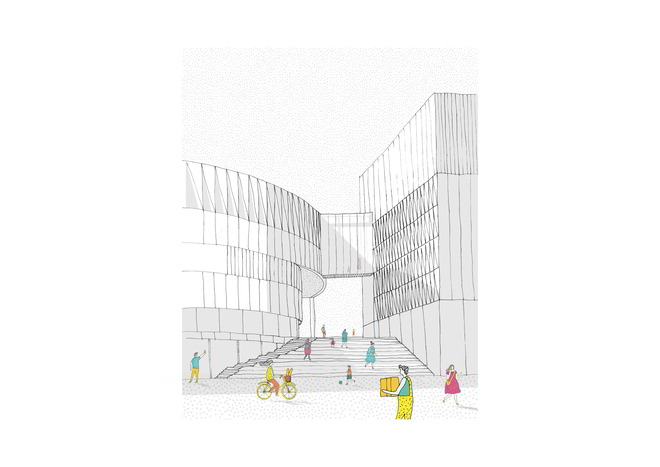

Weiterhin herausragend im Entwurf ist, im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes, eines der Eckgebäude. Größer in der Vertikale als die Arena und gelegen an einer Straßenkreuzung, markiert es die Position der ehemaligen unscheinbaren Bierstube und erhebt sie zur wahren Gastronomie. Zum Restaurant gesellt sich ein Hotel dazu und (bei dieser Gelegenheit) ein Fitnessstudio und Büros. Auffällig an diesem Baukörper ist seine wie aufgeständert wirkende Konstruktion. Es entsteht ein luftiges Erdgeschoss mit offenem Grundriss. Die darüberliegenden fünf Etagen (einschließlich die zuoberst liegende Halle) ruhen somit auf einer durchgehend verglasten Eingangsebene. Ihre großzügige Raumhöhe und Transparenz erlaubt es den Passanten, die nebenanliegende Arena nahezu ungestört wahrzunehmen. Besonders bei Nacht entsteht der visuelle Effekt, dass beide Bauwerke ineinander übergehen.

Und damit ergibt sich das Thema der Anbindungen. Denn die bewusste Entscheidung für klar formulierte Einzelbauten bringt zwangsläufig auch Zwischenzonen mit sich. Ihre Überwindungen und Gestaltungen sind wichtig für eine reibungslose und ansprechende Zirkulation. Die Architekten lösen das Problem mit Freiluftstegen, Grünflächen-Design und den zwei Treppenanlagen im Außenbereich. Letztere dehnen sich zwischen den Gebäuden aus und fließen gleichsam von der höher gelegenen Ebene des Grundstücks in die Tolstého Straße ab. Damit glückt ein weiterer Schachzug: die Kommunikation der Mehrzweckarena Jihlava mit der anderen Straßenseite. Hier steht, recht konfrontativ, die geschlossene alte Fassade der Polytechnischen Hochschule. (Das heute pädagogisch genutzte Bauwerk ist ein Gerichtsgebäude von 1905.) Es fällt nicht schwer, sich vorzustellen wie die Studierenden den architektonischen Neuzugang beleben werden.

Der Dialog ist gewollt und beschränkt sich nicht allein auf eine bestimmte Straßenseite oder allein auf eine Generation. So ist der Smetana-Park quasi das grüne Pendant zur steinernen Universität. Er liegt zum Stadtzentrum hin und bietet eine weitere Gelegenheit, Besucher – und damit auch mehr Senioren und Kinder – anzulocken und aufzunehmen. Der neue Entwurf für die Mehrzweckarena Jihlava wirkt gleichsam als ein Sammelbecken und Verteiler zwischen dem Stadtzentrum und den anliegenden Bereichen. Was hier vor allem entsteht ist ein Flair von Campus.

Chybik+Kristof machen aus einer vorher kaum lesbaren Baustruktur einen neuen Beitrag für das urbane Leben, eine Begegnungsstätte für unterschiedliche Gesellschaftsschichten. Für eine Stadt dieser überschaubaren Größe ist das eine beachtliche und geschickte Investition. Investiert wird aber vor allem in die Identifikation der Menschen mit diesem Ort. Und hier rückt die Fassade in den Mittelpunkt.

Hervorstechend in der Oberflächengestaltung ist die warme rote Farbe der Arena. Teils im Innenraum, teils auf seiner rundgeformten Außenhülle signalisiert das Gebäude mit seinem Bordeauxton den dazugehörigen Verein HC Dukla Jihlava. Denkbar ist aber auch, dass diese Farbe die Dachziegel der Altstadt widerspiegelt. Was das Material betrifft, verraten die Entwurfsdarstellungen nur mehr oder weniger perforierte Platten, die bei beleuchteten Räumen für unterschiedliche Schattierungen sorgen sollen.

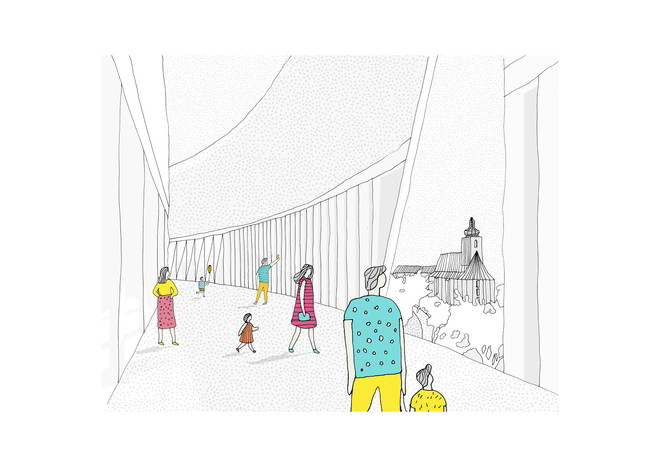

Das zweite auffällige Merkmal der Gebäudehülle sind die „Schrägstriche“. An strategischen Punkten imitieren sie zurückgezogene Vorhänge und bilden Rahmen für die Glanzlichter der Stadt. (Diese Strategie hatten die Architekten bereits bei ihrem Projekt House of Wine angewandt, bei dem sie eine alte Brauerei mit Öffnungen durchsetzt hatten, die die Aufmerksamkeit der Besucher auf bestimmte Ausblicke lenken). Aber ist das genug, um die diagonale Anordnung zu rechtfertigen? Woher stammt die Idee der gezackten und spitzen Formen? Welchen Zweck haben all die Reihen von Dreiecken, die nicht nur die Arena, sondern auch den Rest der Gebäude bedecken? (Übrigens taucht dieses geometrische Motiv auch in der Fassade des Vorgängerbaus in Form von kleinen ornamentalen Applikationen auf). Die Antwort liegt möglicherweise in dem Fluss begraben, der den gleichen Namen trägt wie die Stadt, durch die er fließt: Jihlava. Denn ihr früherer deutscher Name ist wahrscheinlich nicht zufällig entstanden. Es heißt, dass die Menschen einst die scharfen Steine im Flussbett mit den Stacheln von Igeln verglichen. Angeblich soll aus dieser Assoziation der Name „Iglau“ entstanden sein. Aber wie immer sind der Phantasie keine Grenzen gesetzt: Das Zickzack-Muster an der Spitze der Arena erinnert an die Zinken einer Königskrone, die Zinnen einer Burg, die Zähne eines Fabelwesens. Oder hat hier jemand mit dem grafischen Emblem, das jedes Kind in Jihlava sofort erkennt, Tangram gespielt?

Fest steht, dass diese Gebäudehülle eines nicht verhehlt: Sie hält etwas zusammen. Fassade als Kitt?, ruft die kritische Stimme aus. Fassade als Kleid!, würde Karin Harather2 zu bedenken geben. Und tatsächlich: Das Fassadendesign von Chybik+Kristof erinnert an die Welt der Schneiderei: So wie bei einem klassischen Damenkostüm oder einem Herrenanzug, drücken die einzelnen Teile durch Abstimmung und Kontraste von Materialien, Farben und Muster ein Ensemble aus.

Zum Schluss ein kurzer Vergleich: Eine der größten Eishockey-Spielstätten Europas, die O2-Arena, befindet sich in der Hauptstadt Prag. Ihre silbrig-kühle Ufoausstrahlung steht in krassem Gegensatz zu ihrer Verwandtschaft in Jihlava. Die Architekten haben die Besonderheiten und Vorteile einer kleineren Stadt verstanden und genutzt. Ihr Entwurf für diese Anlage berücksichtigt die unmittelbare Umgebung und bietet eine integrative urbane Struktur. Sie bringt die Menschen zusammen und macht es ihnen umgekehrt leicht, die neue Attraktion in ihren Alltag aufzunehmen. Kurz gesagt, die Mehrzweckarena wird zu unserer Mehrzweckarena. ♦

¹ Die Biografien von Gustav Mahler und Walter Gropius kreuzen sich in ihrer amourösen Rivalität um Alma Mahler-Werfel.

² Harather, Karin: Haus-Kleider : zum Phänomen der Bekleidung in der Architektur. Köln: Böhlau, 1995.

Zur Website von CHYBIK+KRISTOF

Pretty sporty: Jihlava Multipurpose Arena by Chybik+Kristof

Chybik+Kristof makes more of a multipurpose arena. Their competition design for an ice hockey stadium in Jihlava replaces a predecessor building from the 1950s. Not far from the largest square in the Czech city, the new project is giving the starting signal: Curtain up on an urban site with a campus atmosphere and a sense of local identity.

The repertoire of Chybik+Kristof Architects & Urban Designers has been growing continuously since the founding of their office in 2010. From residential buildings to wine cellars, they have mastered various typologies. Their productivity borders on sportiness. All the more fitting is their latest assignment for an ice hockey stadium, which is due to end in 2023 after a construction period of only two years. Their recently won competition gives a new look to one of the largest sports and leisure complexes in the Czech Republic, the Jihlava Multipurpose Arena.

Jihlava? The former Iglau lies almost halfway between Prague and Brno. With a population of around 50,000, it seems to be a place that has been left somewhat at the sidelines. Yet, it has a remarkable and moving background.

The year 1968: Troops of the Warsaw Pact invade Czechoslovakia. The following year Evžen Plocek sets himself on fire in protest against Soviet aggression. The suicide takes place in the middle of the city, on the main square Masarykovo namesti. The toolmaker is only one of several living torches. Time jump, same place: Since the 1980s, a longish building, a meteorite with a built-in McDonald, has formed the center of the city. From now on, the word ‚out of place‘ gets an illustrative representation. After all, the black and white, almost unfashionable and controversial Socialist-era department store Prior has nothing to do with the buildings of various eras (up to the Gothic period) that line the square. A few steps further and almost two centuries back: close to the southern end of Masaryk Square stands the house where Gustav Mahler spent his childhood. The composer is regarded as a pioneer of modernism in music, just like his contemporary Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, who became an important figure for modern architecture1.

This is a suitable springboard to the actual subject. Quasi opposite the Mahler House, across the square with its mixture of historical buildings and loveless architecture of the present and the scene of frightening incidents of recent history a piece of architecture is finally to be created that will bring the spirit of modernity to Jihlava.

But what did the previous sports and leisure complex in the city look like? What is this competition project by Chybik+Kristof supposed to replace? The site presents a building whose main feature seems to be that it takes up space. It squeezes itself between the College of Polytechnics Jihlava (which borders on the outskirts of the city) and the Smetana Park nearby the old town. Since the 1950s, the building has served as an ice hockey stadium. Together with an underground car park, it occupies the whole plot. But here the clarity ends. The structure makes a patched-up impression. The walls are partly brick, and some areas show ochre and Bordeaux red (the club colours). And its entire side front towards the park is glazed. From above, the old complex appears compact. Yet its fragmented roof landscape reveals different spatial zones. Behind the muddled shell, there is also a hockey store and a cosmetics shop. Furthermore, in a corner building, there is a beer bar, the obligatory Club Pub. It is not difficult to recognize: the initial condition of the new Jihlava Multipurpose Arena was confusing.

Chybik+Kristof allow four separate buildings to crystallize out of the amalgam-like predecessor. That enables order and composition. Three of them (partly based on the existing structures) mark out the corners, as it were. In this way, they help to create a framework for the heart of the decentralized complex: a spacious new arena, a monumental construction for 5,600 spectators. This oval hall functions as an ice hockey rink, exhibition and event space and as a concert venue. Its flexibility even increases with the addition of a gymnasium. And there is even the icing on the cake, appropriately enough on the roof: here rests an outer track, which enriches the sporting facilities and offers the people an unobstructed view of their city.

Another outstanding component of the design is, in the purest sense of the word, one of the corner buildings. Larger in vertical dimension than the arena and lying at a crossroads, it marks the position of the former inconspicuous beerhouse and upgrades it to real gastronomy. The restaurant comes along with a hotel and (on this occasion) a gym and offices. The remarkable feature of this building is its structure: It looks like standing on stilts. The result is an airy and open ground floor. The five storeys above (including the hall at the top) rest on a fully glazed entrance level. Its generous ceiling height and transparence allow passers-by to perceive the adjoining arena almost without disturbance. Particularly at night, the visual effect is that both buildings merge into one another.

And this brings up the issue of connections. The clearly formulated, individual buildings inevitably results in intermediate zones. Their overcoming and design are important for the smooth and pleasant circulation in the place. The architects solve the problem with open-air walkways, green space design and the two staircases in the outdoor area. The latter extend between the buildings and flow, as it were, from the higher level of the site into Tolstého Street. This is another successful move: Letting the multi-purpose arena Jihlava communicate with the other side of the street. Here stands, quite confrontative, the closed old facade of the Polytechnic University. (The building used today for educational purposes is a courthouse from 1905.) It is not hard to imagine how the students will enliven the architectural newcomer.

The dialogue is intentional and is not limited to a particular side of the street or one generation alone. Thus Smetana Park is, so to speak, the green counterpart to the stony university. Situated towards the city centre, it offers another opportunity to draw and receive visitors – and with it, more senior citizens and children. The new design for the Jihlava multipurpose arena acts as a reservoir and distributor between the city centre and bordering areas. What is created here above all is a flair of campus.

Chybik+Kristof convert a previously hardly legible building structure into a new contribution to urban life, a meeting place for different social classes. For a city of this modest size, this is a considerable and skilful investment. However, the investment focuses primarily on the identification of the people with this place. And this is where the façade takes centre stage.

What stands out in the surface design is the warm red colour of the arena. Partly in the interior, partly on its round-shaped outer shell, the building with its Bordeaux tone signals the associated club HC Dukla Jihlava. However, it is also conceivable that this colour reflects the roof tiles of the old town. As far as the material is concerned, the design presentations only reveal more or less perforated tiles, which are supposed to provide different shades with illuminated interiors.

The second conspicuous feature of the building envelope consists in its „slashes“. At strategic points, they imitate pulled back curtains and form frames for the highlights of the city. (This is a strategy the architects had already used int their project House of Wine where they had interspersed an old brewery with openings that direct the attention of visitors to specific vistas). But is that enough to justify the diagonal layout? Where did the idea of the jagged shapes and pointy forms come from? What is the purpose of all those rows of triangles that not only cover the arena but also the rest of the buildings? (By the way, this geometric motif also appears in the façade of the previous building in therms of small ornamental applications). The answer may lie buried in the river, which bears the same name as the city through which it flows: Jihlava. For its earlier German name probably did not come about by chance. They say that people once compared the sharp stones in the river bed with the spikes of a hedgehog – which in German means „Igel“. Allegedly this association gave rise to the name „Iglau“. But, as always, there are no limits to the imagination: The zigzag pattern at the top of the arena is reminiscent of the prongs of a royal crown, the merlons of a castle, the teeth of a mythical creature. Or did someone play tangram with the graphical emblem that every child in Jihlava recognizes instantly?

What is certain is that this building envelope does not conceal one thing: It keeps something together. Facade as cement? Calls out the critical voice. Facade as a dress! Would make Karin Harather2 think. And indeed: The façade design by Chybik+Kristof is reminiscent of the world of tailoring: just like a classic ladies‘ suit or a men’s suit, the individual parts express an ensemble through the coordination and contrast of materials, colours and patterns.

Finally, a short comparison: One of the largest ice hockey venues in Europe, the O2 Arena, is located in the capital city of Prague. Its silvery-cool ufo charisma stands in stark contrast to its kinsman in Jihlava. The architects have understood and used the special features and advantages of a smaller city. Their design for this facility takes into account the immediate surroundings and offers an integrative urban structure. It brings people together and, conversely, makes it easy for them to incorporate the new attraction into their everyday lives. In short, the multipurpose arena becomes our multipurpose arena.

TRANSLATION BY ÖZLEM ÖZDEMIR

1 The biographies of the two men collide in their amorous rivalry with Alma Mahler-Werfel.

2 Harather, Karin: Haus-Kleider : zum Phänomen der Bekleidung in der Architektur. Köln: Böhlau, 1995.